I’ve been uncertain what to review this week. I’ve read a lot since the last time I checked in, but I didn't finish anything. I started Werner Herzog’s memoir Every Man for Himself and God Against All, but I’m still mired in his childhood (shoeless feet, iced-over outhouses, a bombed city smoldering in the distance) and I want to get further into it before I settle on an opinion—even though I’m betting that, inevitably, it will be positive. Herzog’s brand of transcendental machismo has always been highly appealing to me, ever since I watched Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo as a kid who was too young to really grasp them. I was actually just talking with someone last night about how important Roger Ebert was to me in this regard. His book Movie Home Companion (the first edition) was around my house growing up and was the reason I first checked out Herzog, Cassavetes, and Errol Morris. Thank god for that book.

I also just started I Could Not Believe It: The 1979 Teenage Diaries of Sean DeLear. I’m a little late getting to this, considering the fact that the innermost thoughts of a queer, black, teenage punk rocker in L.A. in the late seventies are deeply interesting to me. I can already tell I’m going to love it. The candor is ripe, the youthful naïveté is charming, and the yearning for a bigger life is heartbreaking. I’ll also point out that I have a form of dyslexia, I guess: I’m bad at picking up on puns. I needed to be told, in the introduction to the book, that “Sean DeLear” is a play on “chandelier.” I mean, duh, of course. It feels both embarrassing and freeing to admit to this blind spot in my reading comprehension.

And then I’ve dug back into Last Days at Hot Slit: The Radical Feminism of Andrea Dworkin. It has been a couple years but, unsurprisingly, I still love it. Has anybody done eloquent anger better than Dworkin? I don’t think so. And the introduction, by Johanna Fateman, is an essential primer on just why Dworkin is such essential reading for anybody—male, female, non-binary… all of you.

But I think the book that impacted me the most this week has been a new monograph of art by Marc Hundley. It’s called The Voyage Out. It was co-published by Canada Gallery and The Modern Institute. Hundley, who I was casually friends with when I lived in New York but haven’t seen in years, meshes text and appropriation in soothing, moody pieces that celebrate greats from Glenn Gould and Frank O’Hara to Paul Thek and Joni Mitchell. It’s a pantheon that he creates with his choices, and there’s a line of gentleness and melancholy that runs through it all. This work makes fandom feel diaristic, even though it’s more often voyeuristic.

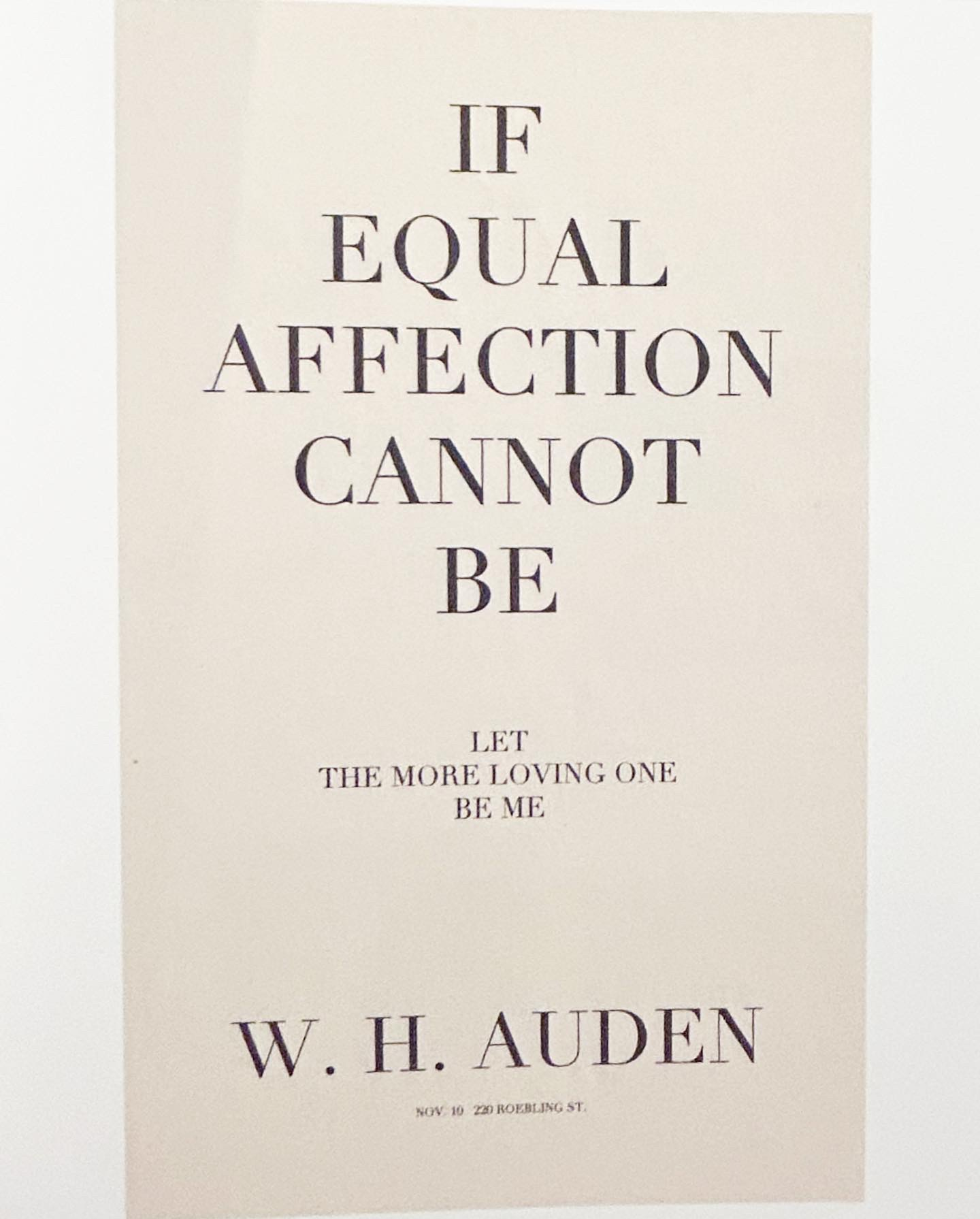

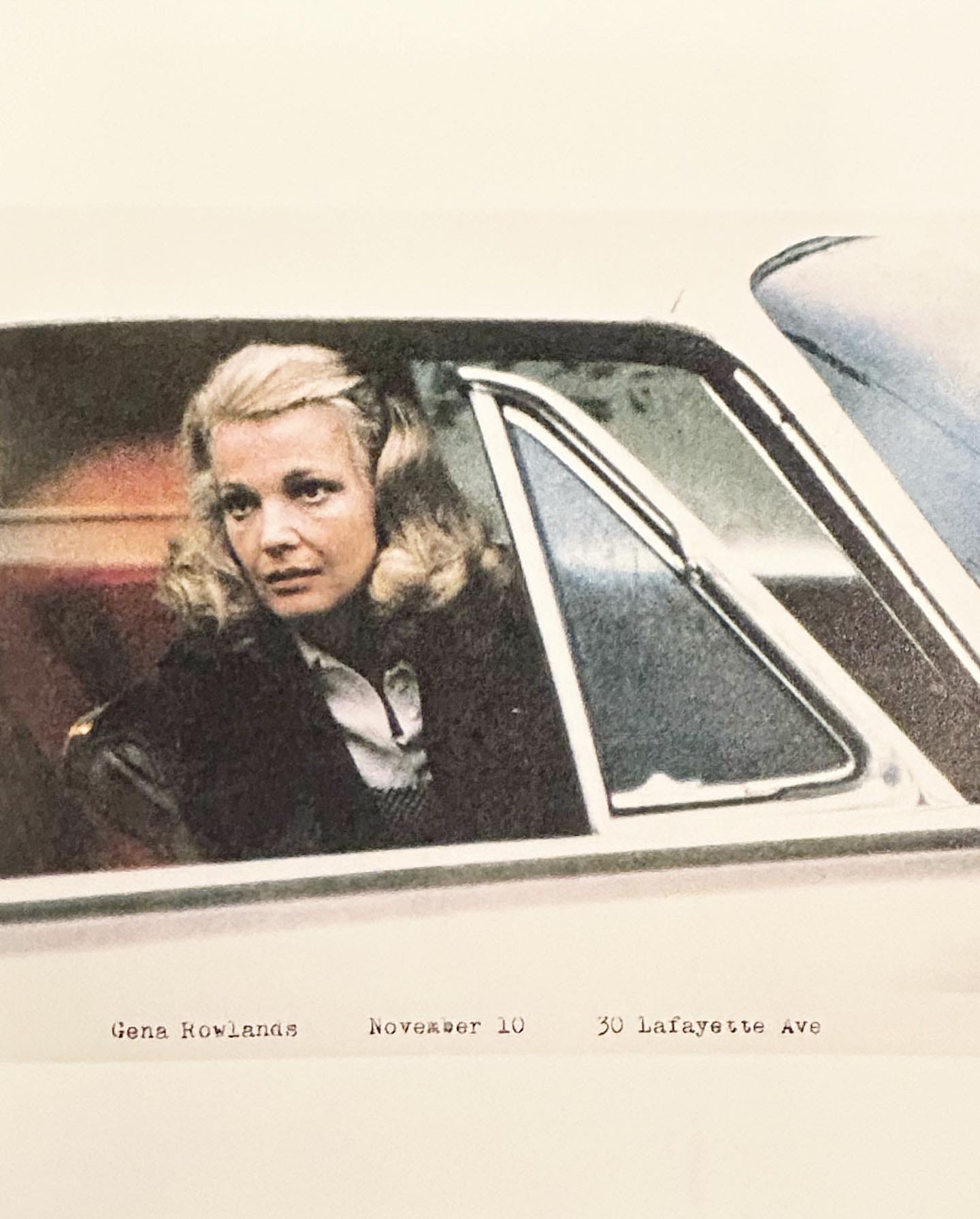

A photo of Joan Baez or a piece of a Rilke poem will be accompanied by an address that has personal significance for Hundley, such as his own home or the location of a bar where a friend threw a party. Did June Tabor, for example, perform at 83 Grand Street in New York City in 2011? No. But in Hundley’s reckoning, something links the person and the location. It’s a way of claiming the subject and making them part of Hundley’s life in a way that another sort of fan portrait can’t, or won’t. The Tabor piece is text-only, yet I can’t help but see her face when I read it. In this way, it’s more successful as a portrait than many traditional ones. And this portrait of Morrissey, for which Hundley chose and aged a picture that hovers between yearbook photo and mugshot, captures something of the subject that I’ve never seen elsewhere.

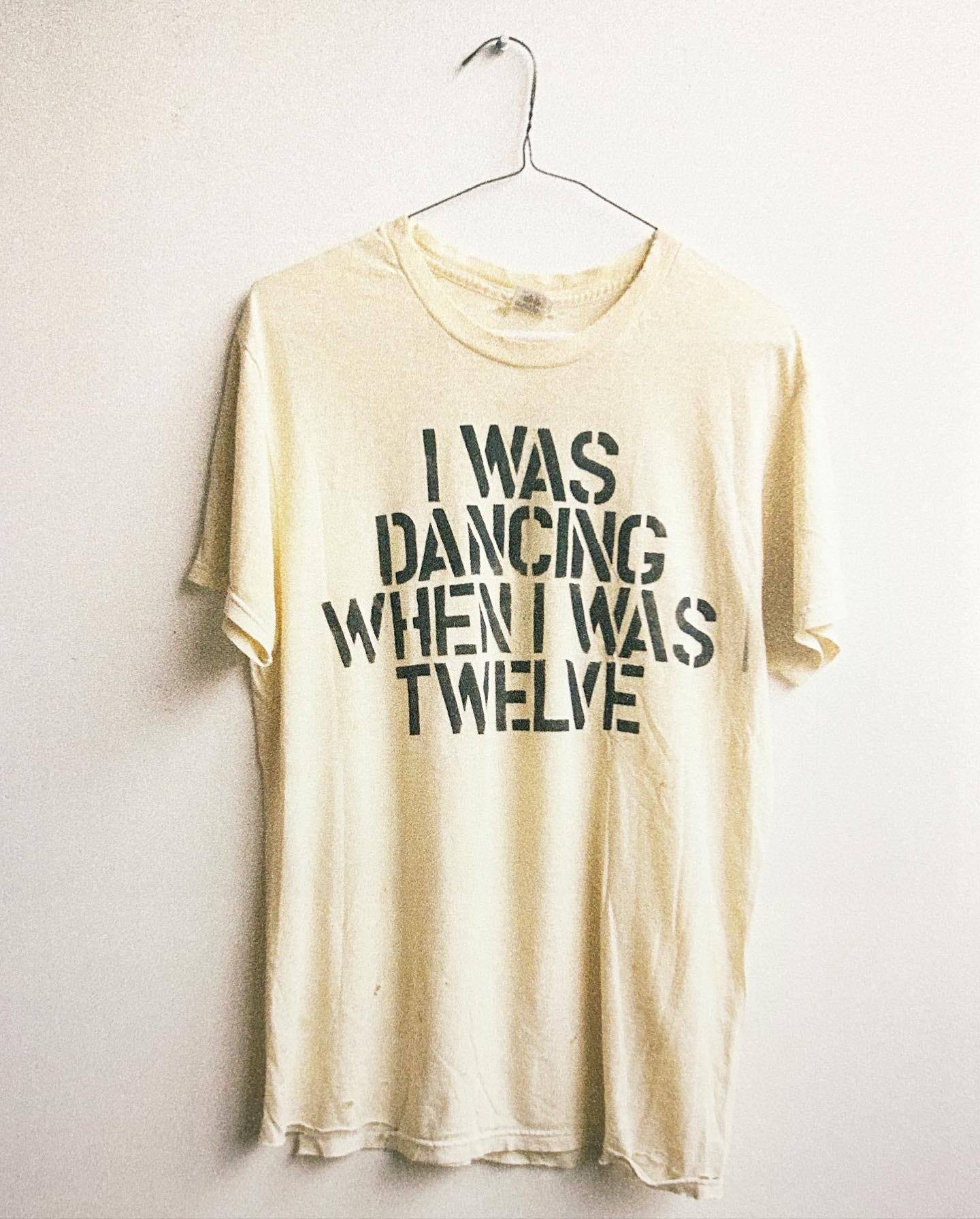

Text is essential to Hundley’s practice. His earliest works were t-shirts that featured lyrics to a song on the front and, often, the name of the band or artist on the back. The cool thing about these is that they make you, the wearer, into the “I” that is speaking the words. I was actually wearing a Hundley shirt on 9/11/01, and it was an inopportune choice in retrospect. The band? The Clash. The quote? “I’m So Bored with the U.S.A.” In wearing it, or when anybody wears a Hundley shirt, we embody the voice of the music. We wear, in a way, the skin of the musician. This, of course, is an ultimate fan fantasy.

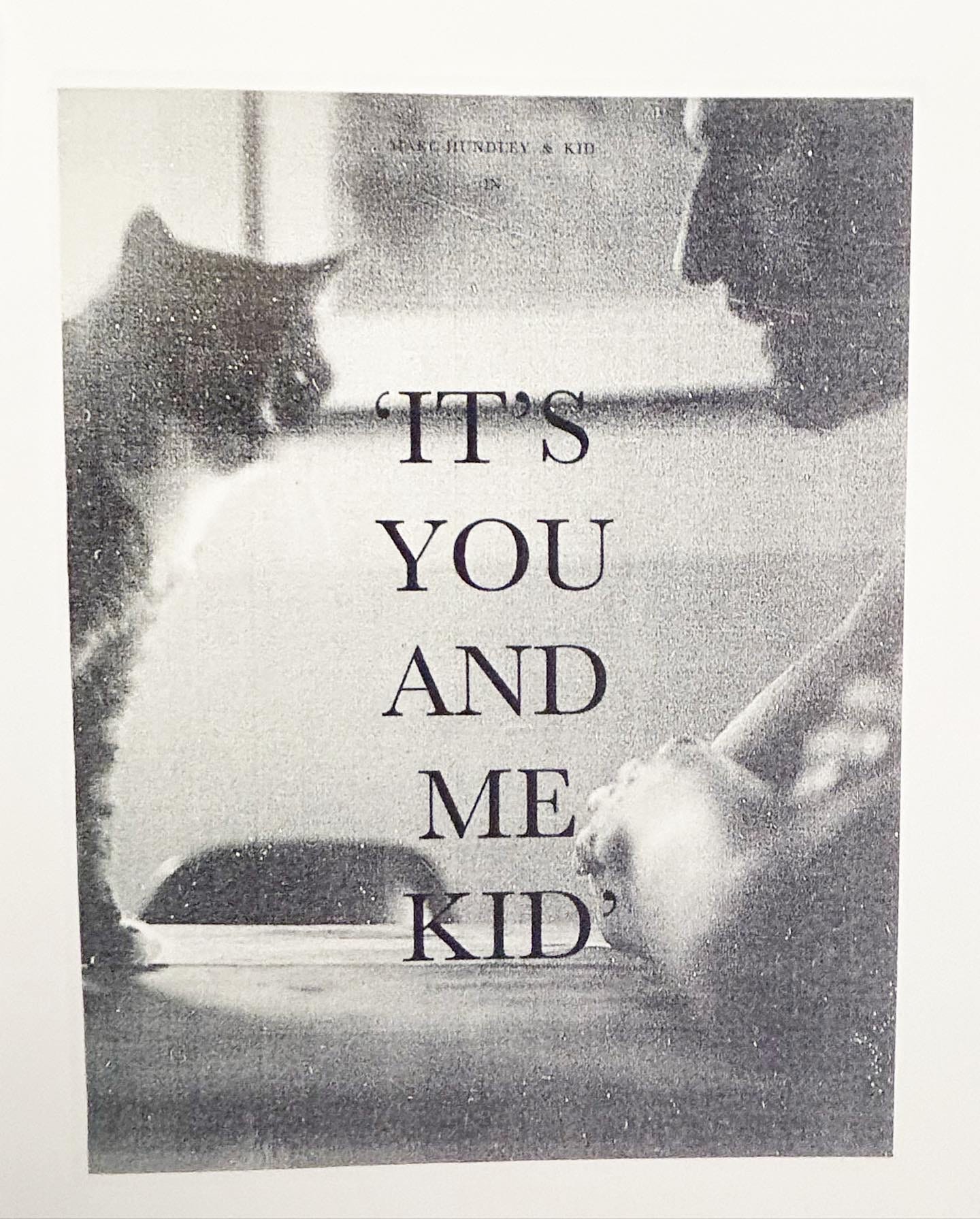

Hundley’s sense of space and ratio is elegant. In another life, he could have been an excellent graphic designer. Thank god he chose to be an artist instead. We have enough graphic designers already. We see the influence of album covers and posters advertising The Smiths in many pieces here. Some of his works look like book covers; some look like movie posters. There’s an uncanniness at play in using these ubiquitous commercial formats as vehicles for such personal art.

The cumulative effect of Hundley’s book is one of warmth. By sharing his loves with us in such finely crafted works, he brings us inside him autobiographically. There’s both a hiding and a vulnerability at play in the work, although sometimes—such as when he features a beloved cat—the result is moving to me in a way that makes me feel closer to Hundley as a person. This book is not just a monograph, but also a memoir.

PS: I should really end this entry here, but I have to include one more piece just because I love the subject so much:

Marc Hundley had a show in Guerneville CA when I lived there some years ago. Kind of startling to see his work (and him) in a small Russian River town. I was taken by the way he quietly stole from lyrics and advertising tropes to give them a kindred, more private reason to be. I'll look for the book.

So many good sentences in here