A quick preamble for those who’ve been keeping score: My chronic illness continued to dog me for a few weeks after my last post, which I hope explains why it’s been so long since you’ve heard from me. But I’ve undergone a tremendously encouraging upswing in the past week or so, and I’m going to choose to err on the side of optimism and say that I plan on returning to a posting cadence here of every other Monday or Tuesday, with occasional quicker dispatches in between as the spirit moves me. Thank you, reader, for your kind patience.

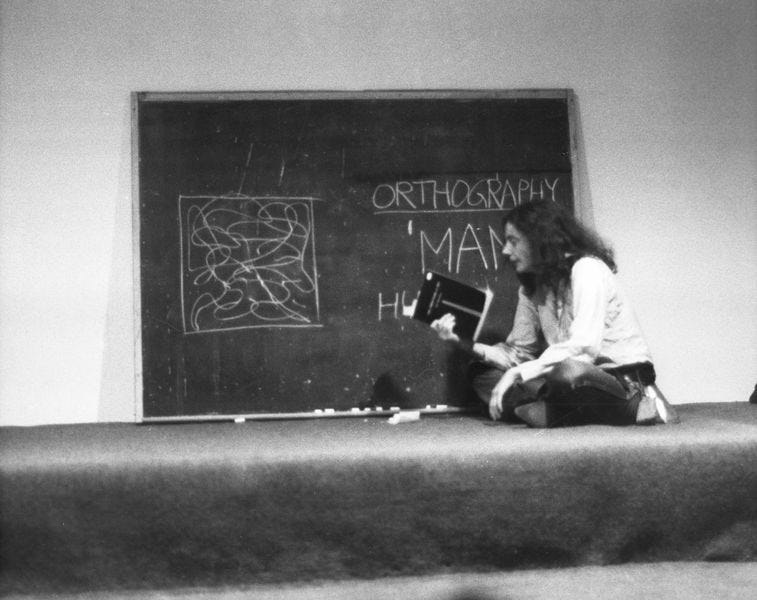

I’ve been fascinated-bordering-on-in-love-with the artist Lee Lozano since my friend, the writer and curator Bob Nickas, showed me around the exhibition of her work he put together at PS1 in 2004. It was my first experience with Lozano’s art, and it blew me away. But perhaps as attractive to me as the work itself was learning from Bob about Lozano’s life and mind.

Much has been written about Lozano, so I’m just going to do my own interpretive, semi-quick pass through her career here and then come to my real point, which has to do with why I’m feeling such a vigorously renewed attraction to and identification with her these days. If you want a more in-depth overview of her trajectory as an artist, I recommend the forthcoming book Lee Lozano: Strike (Marsilio Arte, 2024).

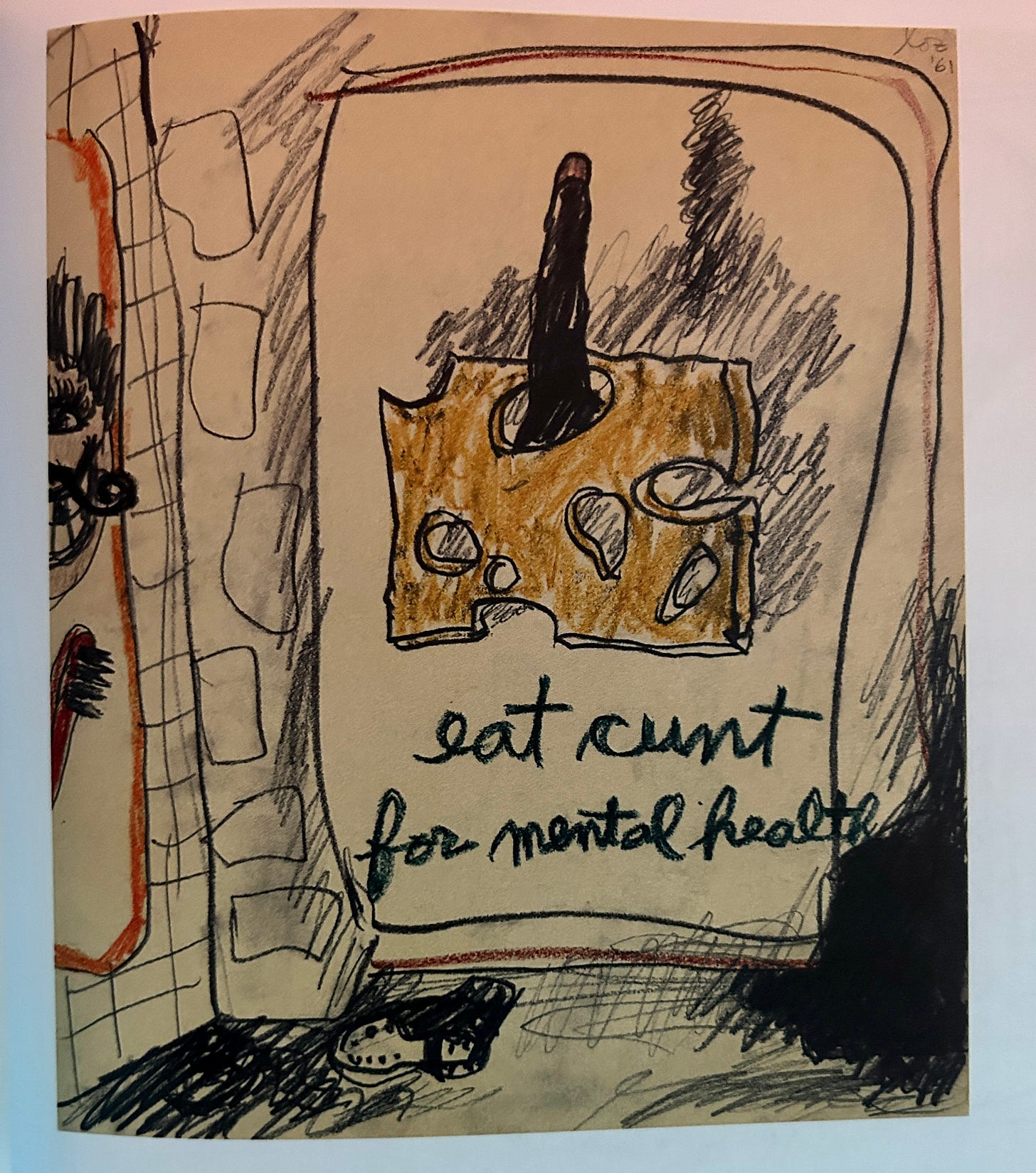

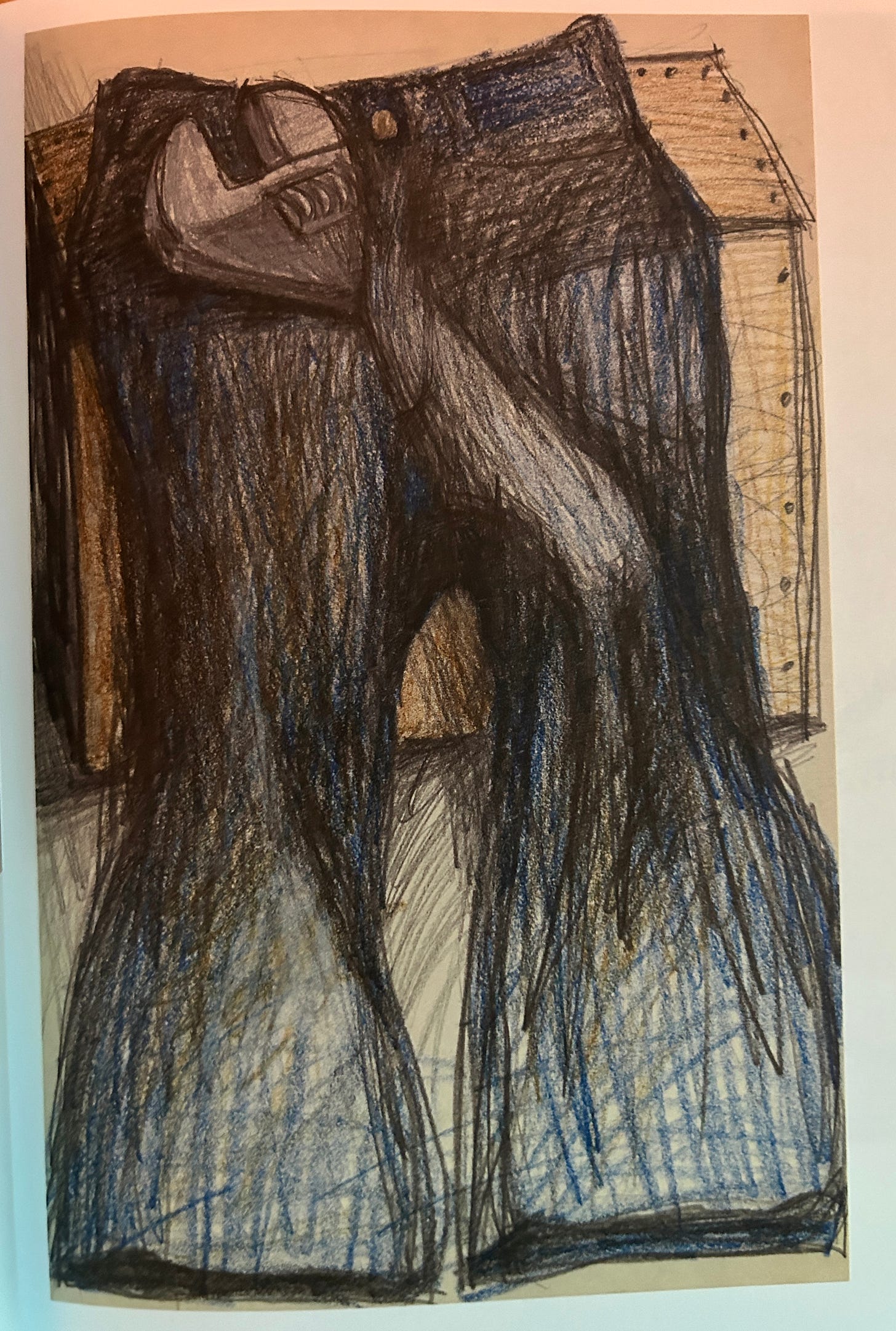

Lozano’s drawings from her early years in New York City, when the 50s were becoming the 60s, are startlingly unique and, in their boldness and jubilant vulgarity, ahead of their time. There’s something sophomorically sexualized in much of them, but even when she’s disembodying penises and scrawling seemingly angry texts above bare asses, there’s a weirdly joyous, childlike exploration at play. These drawings have the energy of an id set free to smear, laugh, explore, and even to arouse itself. They are puerile and pure in their approach to the body, but, with the addition of depictions of various tools, an element of complication and commentary is layered into the whole affair. A phallic drill bit in extreme close-up, a pencil sharpener with a somehow inviting cavity, a fetishized pair of jeans with a wrench sticking out of the fly where another kind of “tool” generally protrudes… And then there are the drawings, some from as early as 1961, that match wildly rendered scenes with snippets of ribald text. In one of these, a little brown stalagmite (which could stand for any number of things) emerges from a hole in a slice of Swiss cheese below a text that reads “eat cunt for mental health.” This wonderful piece was a portent for the drawings that were about to pour forth from Lozano, in which visual and textual puns collided in ever more scatological, hilarious explorations.

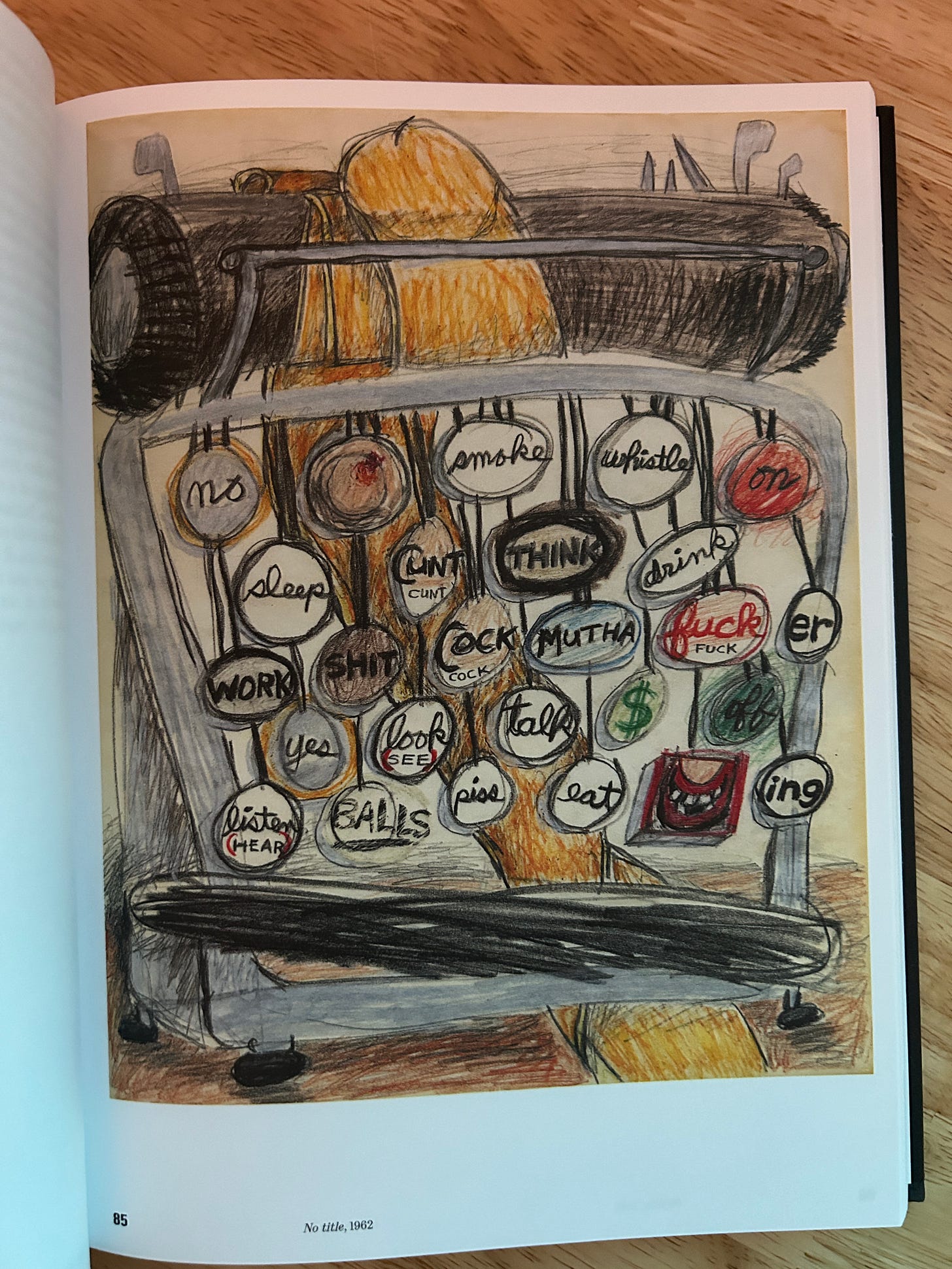

No title, 1962, an early masterpiece, affords us a glimpse at Lozano’s arsenal of so-called bad words, ranging from classics such as “shit” and “cock” to truly offensive utterances such as “work” and “no”—all depicted as the keys on a typewriter that has a flattened dick rolling through its platen. By hammering out these wonderful, foul words in whatever combinations, Lozano is writing the body.

Another piece from the same year sees a box containing a penis and two disembodied female breasts. Emblazoned above this jumble of parts in confident, sloganistic text are the words: “cocks! cunts! tits! balls!” The words have a shouted-from-the-mountaintop quality to them, as if Lozano had been given a megaphone that had the power to summon the entire world’s attention, and this was her message. What lies behind it? I’ve spent years since I first saw this work trying to puzzle that out. Today, I’ve landed on seeing it as the distillation of a kind of rage that’s tinted with glee. And isn’t apoplectic anger sort of slapsticky and clownish? There’s something consanguineous about fits of ire and paroxysms of laughter. Both represent losses of control, unmitigated dispatches from the interior. I see something of this in Lozano’s “cocks!” and “cunts!” here. Maybe it’s a tantrum; maybe it’s a jubilation—but, either way, it has a primal depth that defies eloquence.

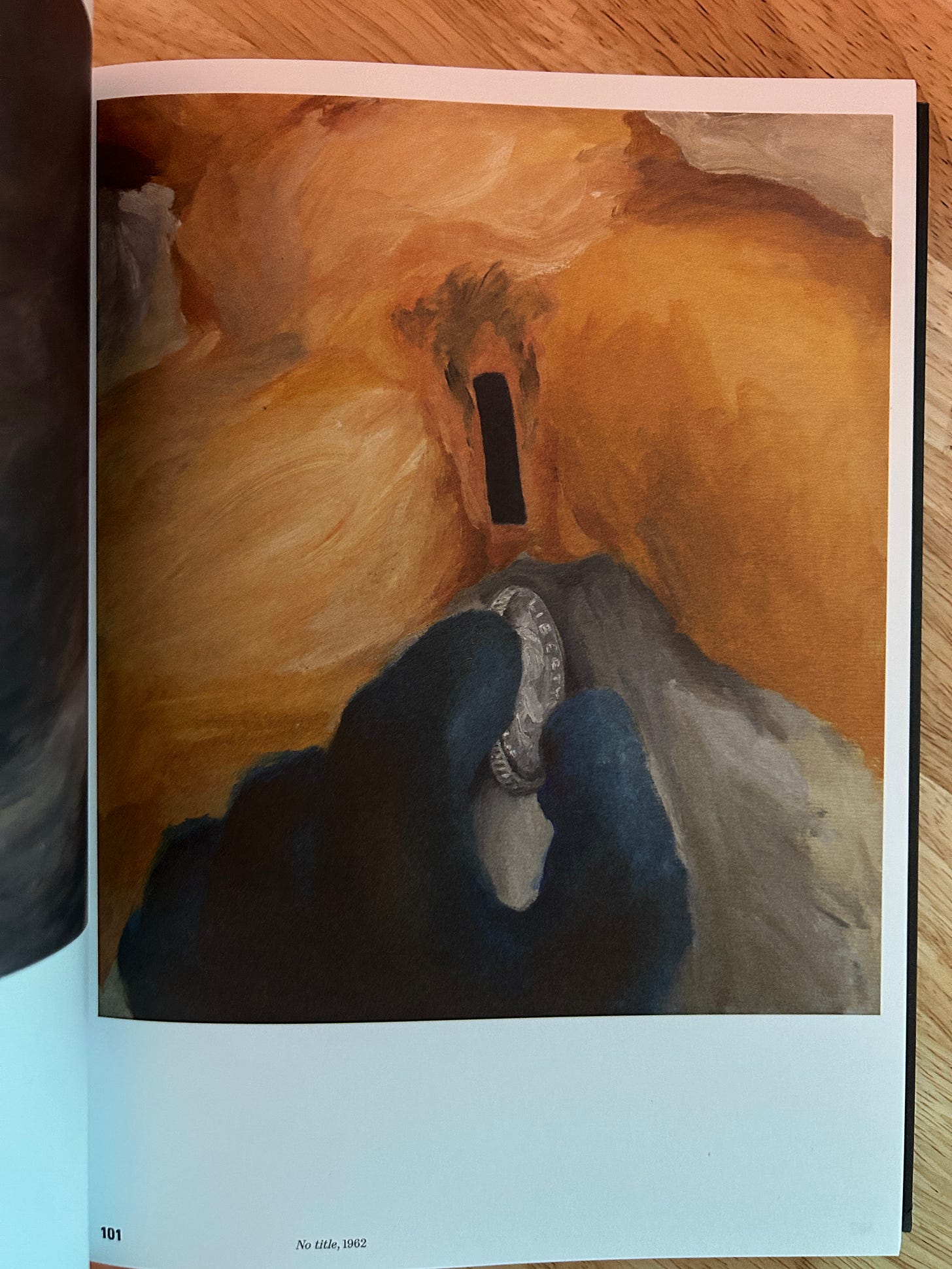

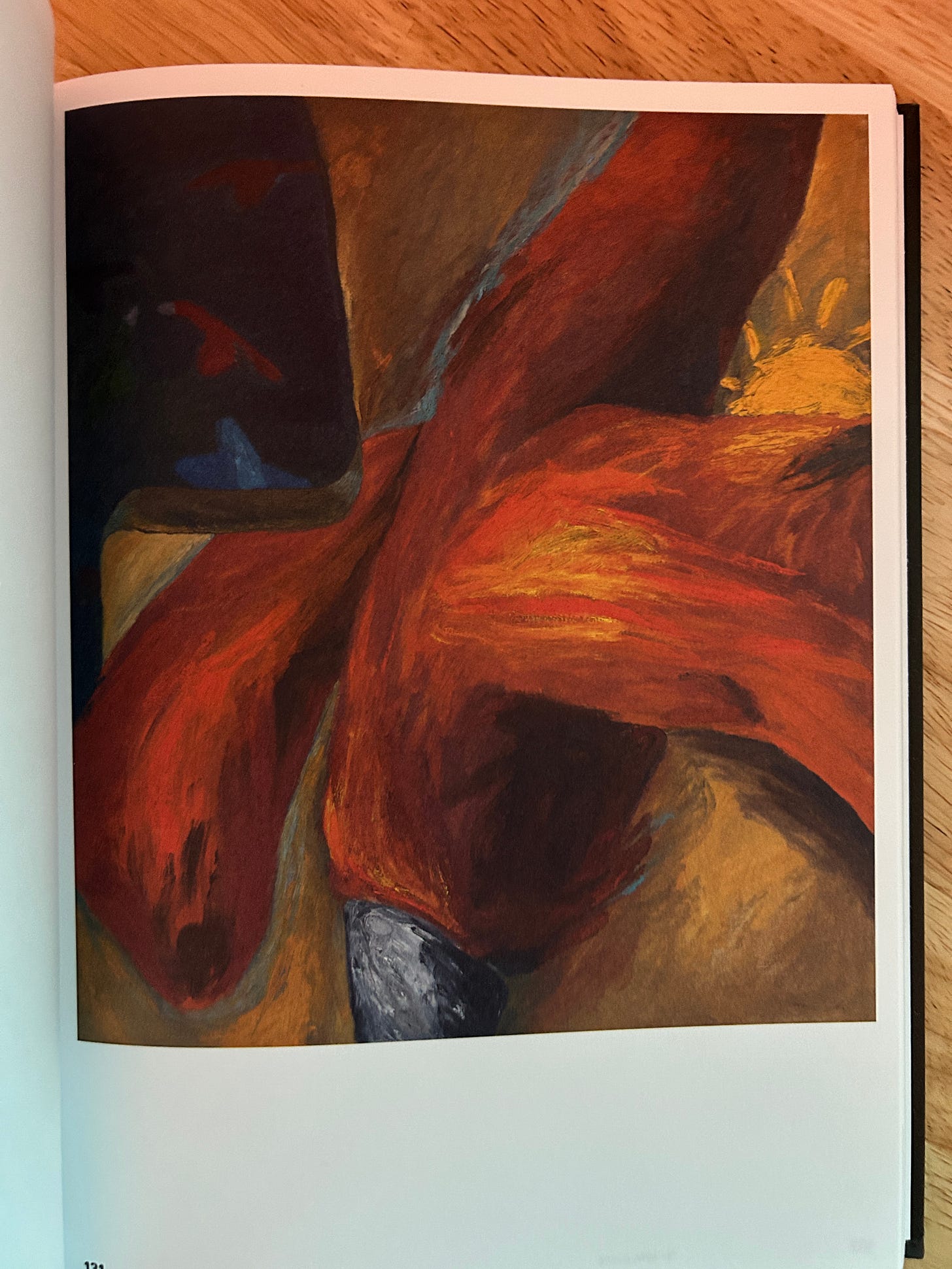

Next comes a body of work in which Lozano displayed her mastery of paint. Again meshing bodies with implements, these fleshy, smeary, sensual figurations are exemplified by another masterpiece, No title, 1962, which depicts a nude female body visible from the waist to the thighs, the vagina morphed into a coin slot. From the bottom of the frame, a hand reaches in, ready to deposit some currency. What sort of action will this money elicit? What exactly is being paid for? The potential implications are such that I dare not approach them in something as ephemeral as a Substack newsletter. That’s not a copout; it’s an admission of powerlessness in the face of this artwork. This is the kind of thing I’d rather talk about with you in person, so let’s just do that one day.

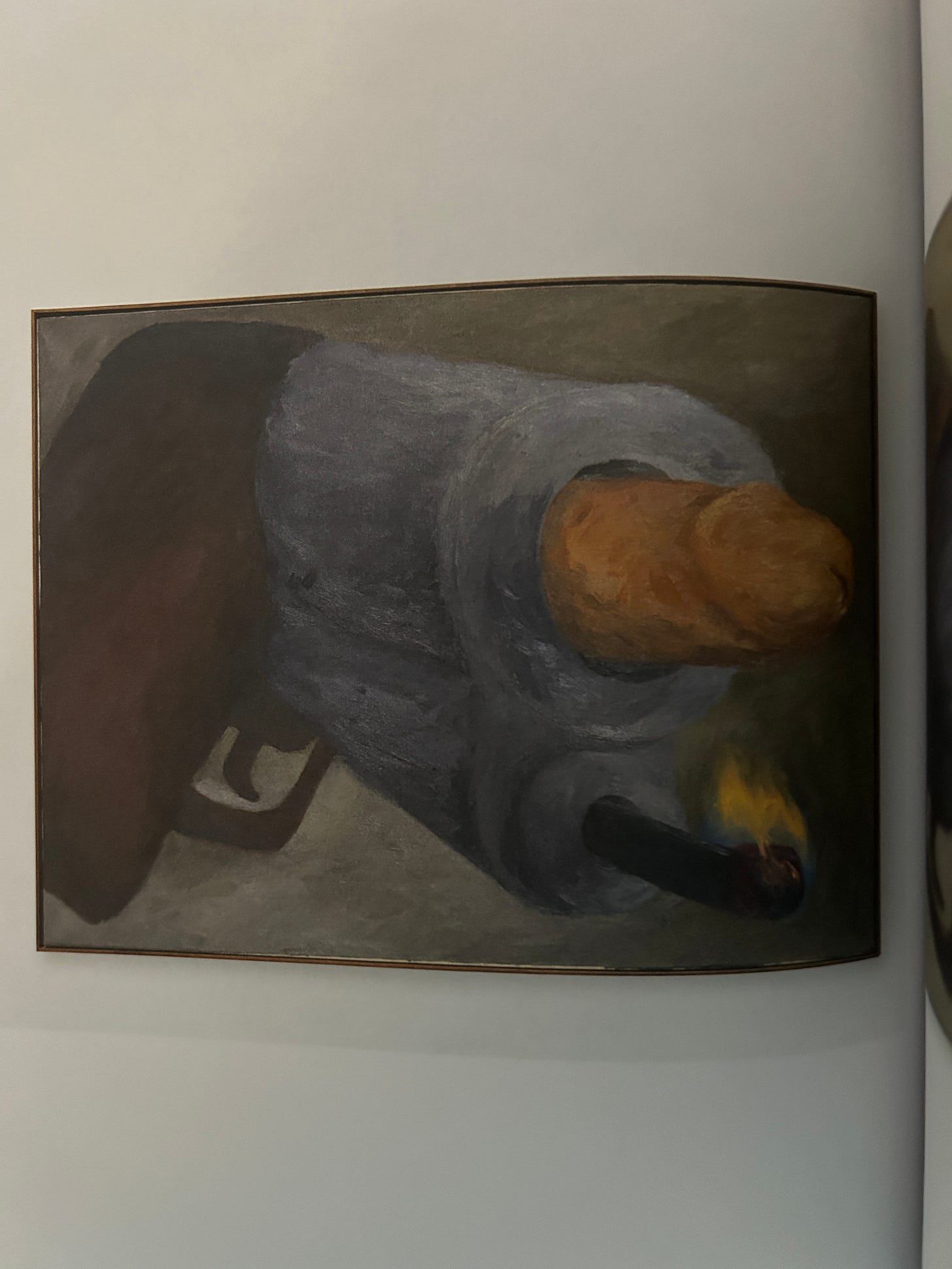

In another piece from this era, the head of a dick and a lit match emerge from the dual barrels of a pistol. As an allegory of explosive male power and destruction, it’s potent. But the echo of the piece, for me, is in the question of what happens to a bullet once it is spent? It becomes a worthless slug of metal. Perhaps there’s something happening in this painting that illustrates the non-renewable nature of masculinity. Once it’s shot forth, once it’s down on the table, perhaps it’s made impotent by being laid bare to the light in a kind of post-coital weakness. I don’t know, I don’t know. I’m really just riffing here.

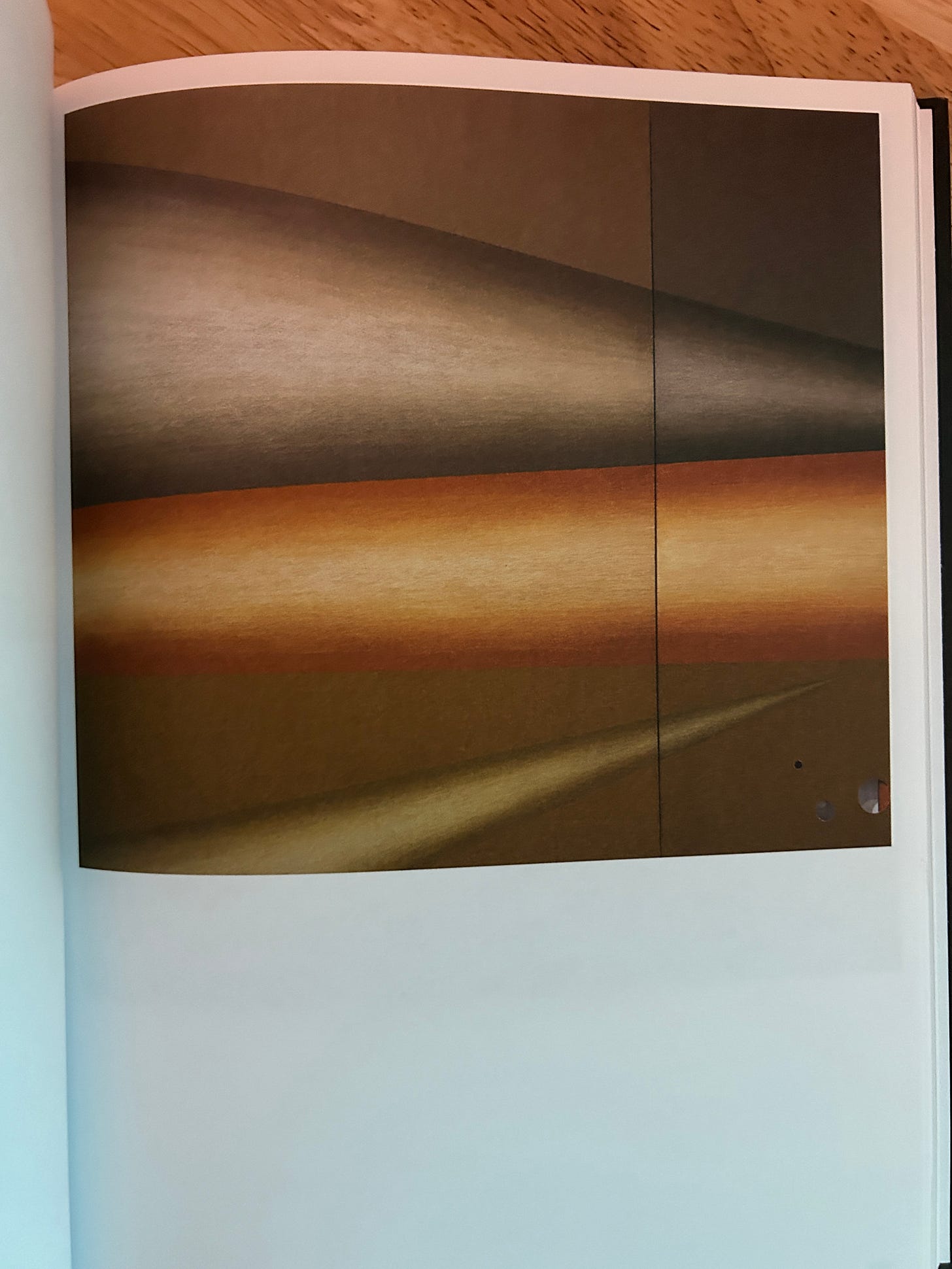

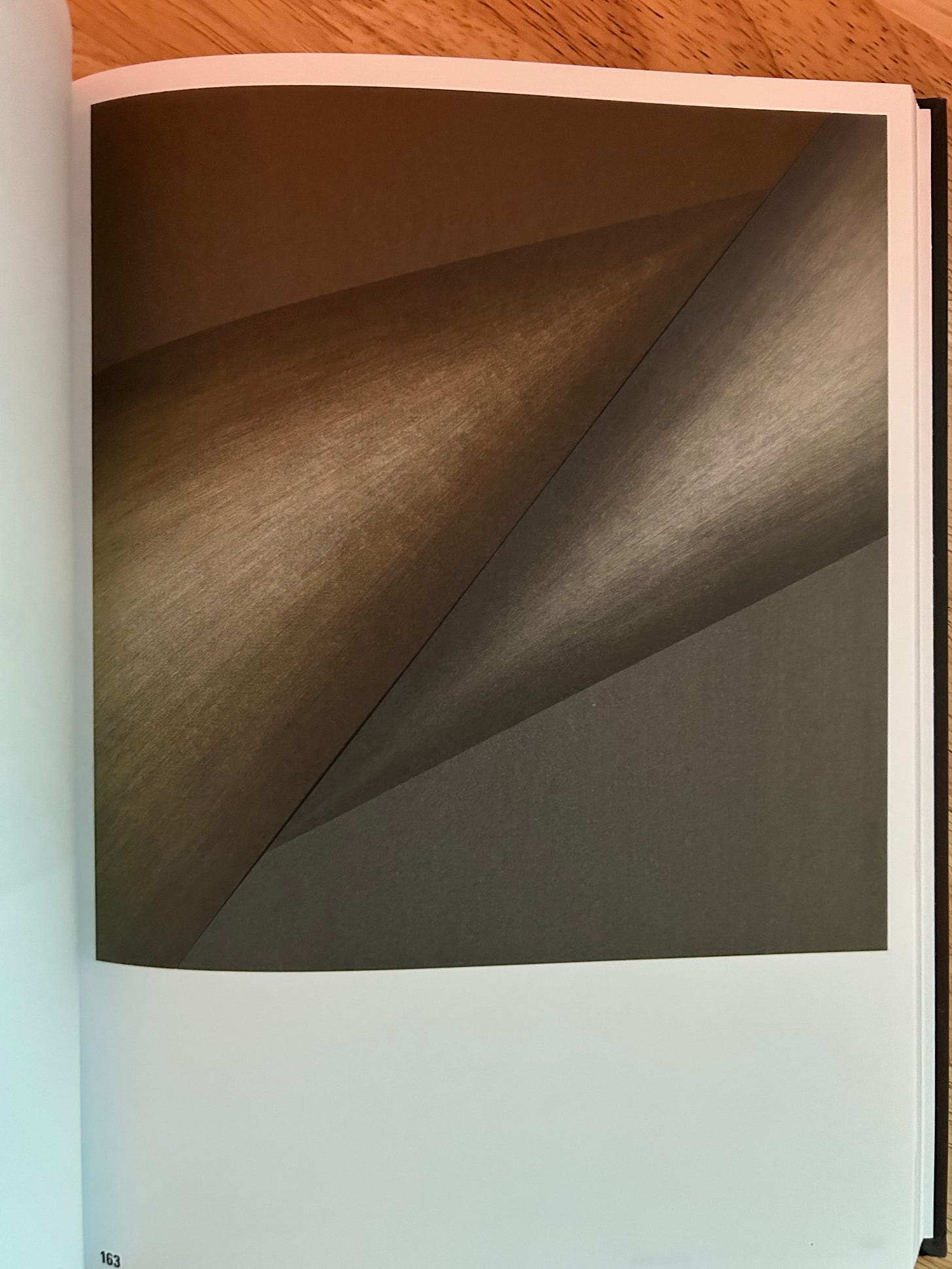

What I see when I stroll through these accumulated eras of Lozano’s work is the evolution and refinement of steadfast messages, but also a restlessness. There are words and then there are no words. As she followed the breadcrumb trail left by her muse, Lozano progressed to massive semi-abstractions that suggest skin and viscera, such as No title, 1962-3, and then truly monumental renderings of, again, tools. Here, Lozano turned household utilitarian objects into uncanny tribal totems. Nuts and bolts; hammers and bits writ large, imposing, even threatening, as in No title, 1963.

Soon after this, Lozano melts into a dimension of pure abstraction, leaving behind language and speaking instead in color and shape. Witness No title, 1965 or Clamp, 1965. But these spooky, vaguely industrial canvases soon give way to their total opposite: an art of words, of unalloyed language, and then, further on, an art of action or, in its most notorious manifestations, of non-action.

But, wait, you know what? I realize now, as I’m coming to the most radical shift in Lozano’s life and work, that this is a two-part thing. Not only do I want the next era of her output to get its due space, but I also want to buy a little more time to formulate just how much her late-career actions and decisions mean to me right now—and how much they could, and perhaps should, mean to all of us, all the time. So: Please tune in next week for this installment’s conclusion…