A few months ago, I wrote about my friend and frequent collaborator Richard Kern for an Italian magazine that was doing an issue dedicated to him and his work. They asked me to focus on his early films. It looks like they’re having distribution troubles (or something) now, so I hereby post the piece… essay… memoir… here because it was fun to write and I want you to see it…

As a teenager in the early ’90s, my first solo trip to New York City from my hometown in South Jersey (to visit a punk-rock penpal who lived in Queens) involved a handwritten to-do list that I really wish I still had today. Among such items as “touch the Krishna tree in Tompkins Square Park,” “buy House singles at Dance Tracks in the East Village,” and “survive an Agnostic Front hardcore matinee at CBGBs” there was an equally important task that would turn out to have a lasting impact on my life: “see some R. Kern movies at all costs.”

R. as in Richard, that is. Back then, after initially knowing his name only via his association with Sonic Youth (cover art for their albums EVOL and Sister, a music video for the song “Death Valley ‘69”) and fleeting fanzine mentions of his sexually explicit, nihilistic, and violent movies, I was veritably gagging on my desire to get my eyes on an R. Kern (as he was then known) film. The friend I was visiting was happy to accommodate this lust, and she guided me via subway to Mondo Kim’s on St. Mark’s Place (my first of hundreds of visits there to come), where we rented a bootleg VHS compilation of Kern movies, which we later watched surreptitiously on her parents’ VCR after they went to bed.

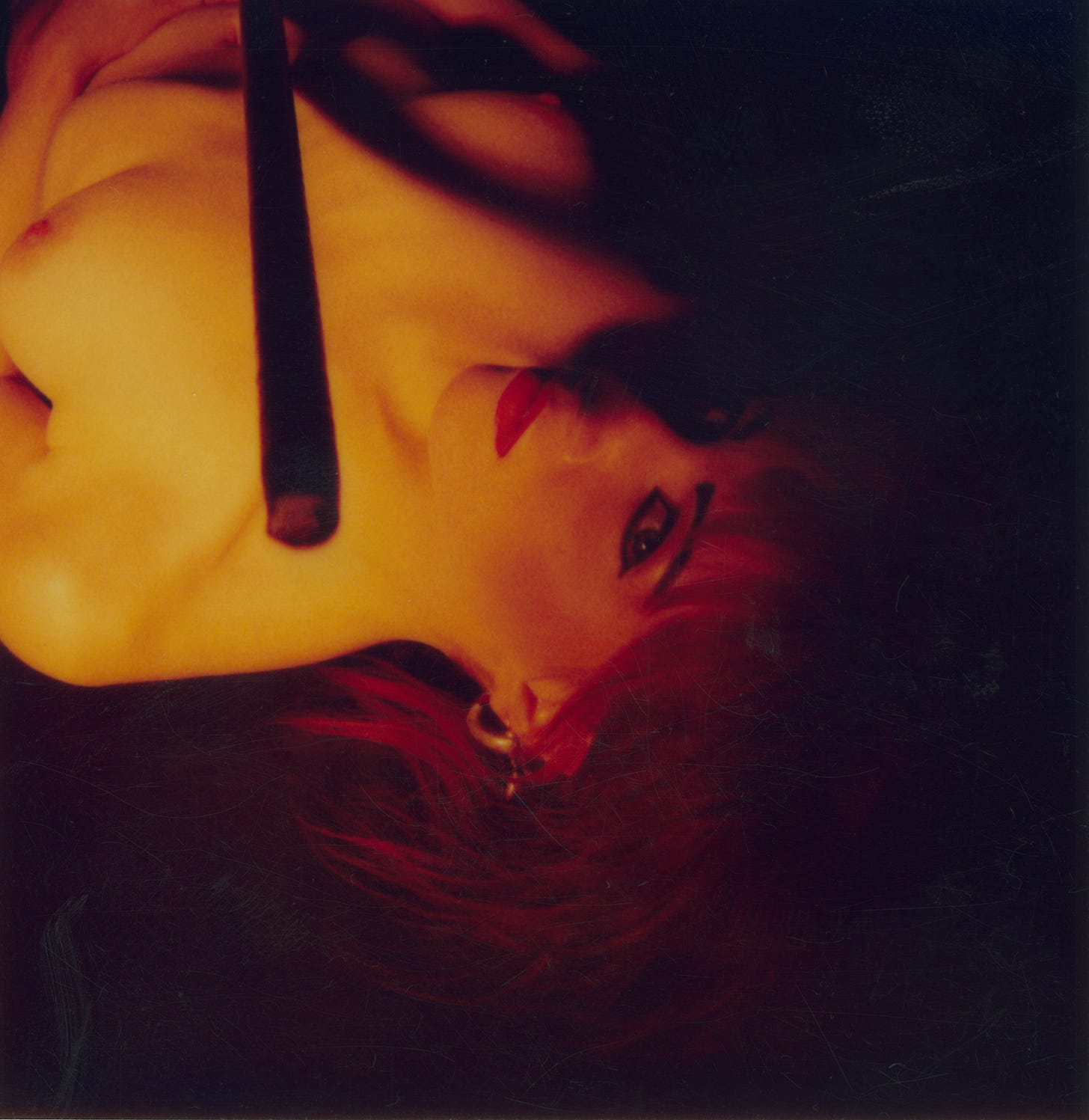

This was my first time seeing such bonafide Kern classics as Fingered, You Killed Me First, and Stray Dogs, and they more than lived up to their reputation. Harsh, sexy, and thrilling but also, and this is an essential part of Kern to me, funny and smart. What I didn’t know then was that he had already, by the time I was getting my first glimpse at his movies, transitioned his focus to still photography—specifically dealing in nude portraits of the sorts of women who populated the demimondes that I, a teen punk dork, yearned to enter. And, lo, more than a decade later, when I was living in New York and working as the editor-in-chief of Vice magazine, I started to publish Richard’s work and direct a web series called Shot By Kern in which we documented his photo shoots. Richard and I quickly became close friends and remain so to this day, but there will always be an alterna-teen inside me that’s totally pumped on my adult proximity to the R. Kern.

Richard’s first movie (but not his first artistic utterance; he’d been cranking out his fanzines such as The Heroin Addict and Dumb Fucker since the early ’80s—a compilation book of which I’m editing for release in 2025, as it happens) was the elegiac and electric Goodbye 42nd Street (1983), which he made for $150. “I was really surprised at the response to it,” Richard told me recently. “A lot of people were shocked, and that was exactly what I was looking for. I couldn't believe how easy it was. And as soon as you do one movie, everybody thinks, ‘Oh, you're a filmmaker.’ In fact, as soon as you do anything, you become that thing.”

Richard did become that thing, embarking upon a career of films that have, since their shocking debuts, become canonical underground documents. Inspired by his peers Beth B. and Nick Zedd, Kern released a run of groundbreaking works across the ’80s and early ’90s, forming the backbone of what came to be known as the Cinema of Transgression, a New York-based microgenre of artists making movies utilizing varying degrees of provocation, prurience, and pretension. The gang also included directors Tessa Hughes-Freedland, Tommy Turner, and more. “The name and idea for the Cinema of Transgression was Zedd’s,” Richard says. “He told me, ‘They'll have a label for us, and that's the way we get into the history books.’ And he was right.” Besides, if the film hustle hadn’t panned out, Richard was already a successful entrepreneur dealing in the finest Hawaiian marijuana imported to Alphabet City.

Richard cultivated a circle of stars in his films, either figures that were also known for their own parallel efforts, such as the No Wave musician Lydia Lunch and the firebrand artist David Wojnarowicz, or unknowns that Kern elevated to icon status, such as the actress Lung Leg, who was basically Edie to Kern’s Warhol or Hanna Schygulla to his Fassbinder. My favorite of Richard’s early films, You Killed Me First (1985), features Leg and Wojnarowicz, along with the artist Karen Finley, as members of a deeply dysfunctional nuclear family. Heavily plotted and hammily acted, it remains hilarious, gross, and eerily relevant today. Lung Leg plays the punk daughter to Wojnarowicz’s and Finley’s square, Boomer parents. It ends in bloodshed, as most families do. “It was a well-executed idea,” Richard says. “That sounds terrible, but it's funny.”

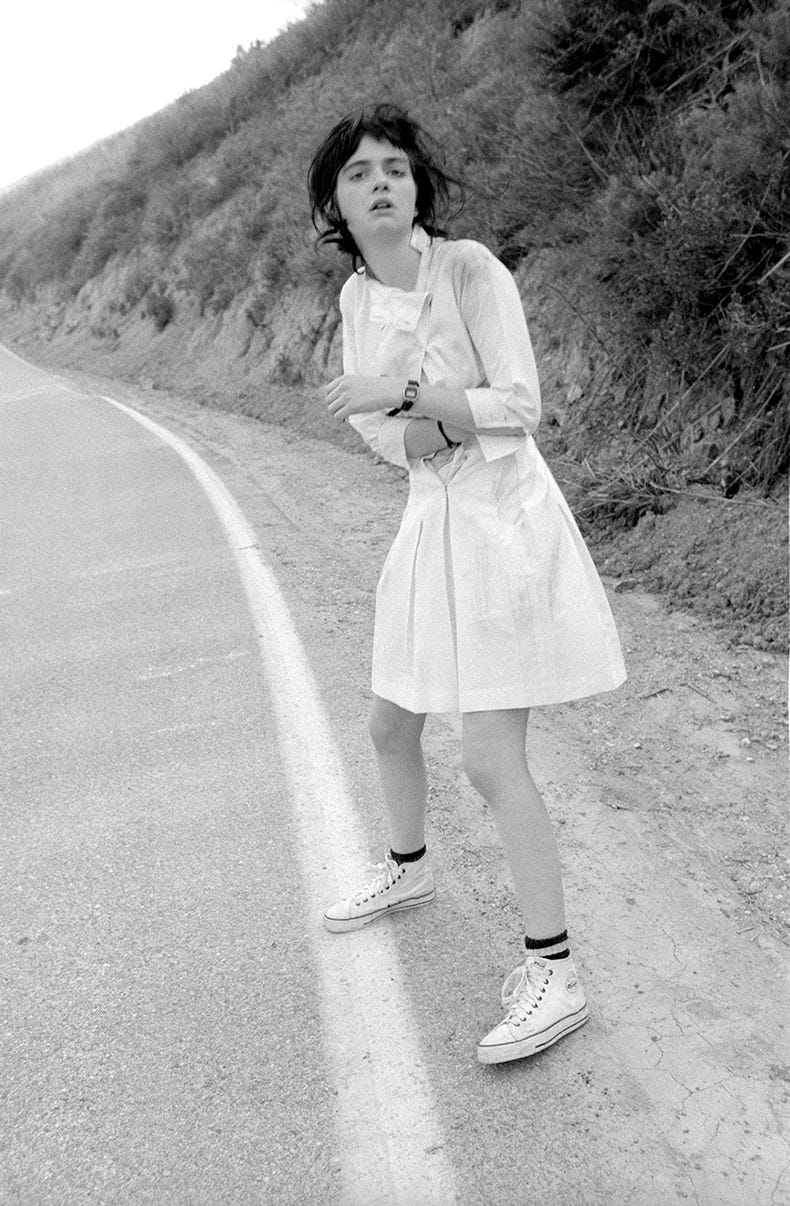

Perhaps Richard’s most prominent film, however, is Fingered (1986), which stars Lydia Lunch and, again, Lung Leg. A road-trip romp concerning a phone-sex operator and one of her clients engaging in various illegal and immoral pastimes, it became something of a calling card for the entire Kern oeuvre. “Things really took off after Fingered,” Kern says. “It caused so much controversy. It got me thrown out of the Berlin Film Festival. It was protested around Europe. But it was also the most technically proficient of my movies. I shot it and then transferred the footage to video, which means the edits weren't sloppy.” Enhanced fidelity only made it easier for audiences to witness the dramatized sex, assault, and general misanthropy on display.

So why did Richard abandon film just as his name was going from emerging to established? It’s true that he quit doing drugs around the same time. Is there a corollary? “The end of my moviemaking wasn't so much because of the drug lifestyle ending for me too. It's just that I didn't feel like I had much to say anymore. I don't have a message these days.” But, perhaps inevitably if we think of the frequent evolution from countercultural samizdat to academicized exhibitions, Kern’s films have become foundational artifacts for the generations of artists that came after them. “I never would've thought, when I was doing these things, that they would be in the collection of the MoMA,” he says. “But they bought twelve films from me along with a lot of the documentation and ephemera. I had no idea anything like that would happen. It gives me some legitimacy, I guess,” he laughs.

Looking forward to the zine book! Read that Cinema of Transgression book a while back and immediately dove head first into Kern’s stuff. Really eye opening.