An Interview with Jonathan Ames, Part 2

(cont... ) The Author of Today's Best Detective Novels Speaks With Apology at Great Length and About So Many Things—Including Buddhism!

Part 1 of this lengthy discussion can be found here. I advise reading it first if you haven’t but, hey, if not, here’s the recap: Jonathan Ames rules and he’s writing my favorite crime novel series right now. It takes place in L.A. and it stars a gumshoe with the unlikely name of Happy Doll and, yes, the books are funny but they are also dark, grim, violent, smart, and deeply observant and even moving. So, here we go, Ames and I, finishing up our productive palaver…

Apology: I'm going to do a little cheap psychoanalysis on the character of Happy Doll, and then maybe you can tell me if any of it resonates or if I'm totally wrong. I like that he seeks answers via both psychoanalysis and via Buddhism. Even his love for his dog George could be a kind of seeking. Is he undergoing an internal struggle to integrate his two halves—the one that's prone to violence and that's traumatized, and the one that seeks peace and kindness?

Jonathan Ames: Yeah, that makes sense. I developed a very painful backstory for him. His mother died when she was giving birth to him. He had an abusive father, an alcoholic. And all that has only gotten more layered as the books have gone on. There's a certain same thing with Parker1, where Stark would always re-summarize who Parker was. He would kind of repeat it. You'd get that summary.

Right, which not just reinforced the character but also made any particular book out of the many in the series a potential entry point for a neophyte.

And with Doll, he has this painful childhood, and I think that's something I want to start looking at in the fourth book. It was almost like he ran away from his dad. He goes into the Navy because he's kind of big and strong, but he doesn't fit in. They make him a cop on a boat. Then he comes out, and what's next, what are his skills? Okay, he goes into the police. But wherever he goes, I think he's maybe a little too sensitive for everything. And then he’s a private investigator when we meet him, but maybe for the first dozen years or so of his career, there's not that much danger because mostly—in my mind, again, this is all backstory—he is helping the elderly because he got tied in with a gerontologist. That's, like, his niche. And he barely gets by, but then that dries up. So, for the next three books, he's always broke and getting into these very violent situations. Before the first Doll book, when I created him, he had never killed anyone. Now, suddenly by the end of the third Doll book, he's killed 11 people.

He's “got bodies on him,” as the kids say.

But he's this sensitive guy, and so he's grappling with all this, and there is a side of him that really does struggle to connect with the world. I've been reading this interesting book. It's called The Outsider. Have you heard of it?

Not unless it’s the Stephen King novel.

No. It was a 1950s existential text by this writer who studied artists—mostly all men, unfortunately, because of the time period perhaps. But there’s Hemingway, van Gogh, T.E. Lawrence... It's a sort of beautiful book. It helped me see that Doll is an outsider, which probably reflects my feelings, like anyone who's sort of drawn to books and literature—we are, somewhat, observers.

And being an observer implies a distance if not physically then at least psychically.

Right. One of the early influences for me and for my novel, The Extra Man, was Christopher Isherwood's The Berlin Stories. I think the first piece in it is I Am a Camera.

Oh, yeah. I think that comes from Goodbye to Berlin, the first of the Berlin Stories, right? I loved those.

Yes, right, the originating piece was, I Am a Camera. This goes back to the Anthony Hopkins, Silence of the Lambs thing we talked about earlier: “How do we begin to covet? We covet what we see every day.” It’s that thing of looking out the window. Writers are observers, journalists are observers, poets are observers. Painters, filmmakers, musicians… observers. But writers are real observers. I mean, they must be. I'm not saying anything profound here, And so, Happy Doll is an outsider. I am not going to go there, but at one point I almost had him thinking, ‘Should I write a book?’

Ah, interesting! Which brings up the whole tradition of first-person vs. third-person in crime and thriller fiction. The Reacher books by Lee Child have used each at different times.

What is this first-person narration we’re reading? We don't question it with Phillip Marlowe. Who's he talking to? The continental op? You might imagine these are the reports he filed. But with Happy, I don't want to get too meta. Anyway, like I said, I'm rebooting it all in book four. Doll wants to find meaning. And, to come back around to your question, I think that's the goal with analysis and Buddhism: to find meaning; to make the most of the time we have on the planet with this pressure of death always there. There’s a great passage in Graham Greene’s Travels with My Aunt about how death is lying in this room, in this wall. It is coming closer and closer to you. And what do you do to escape that feeling of being in a cell? It references this thing, which I used as an epigraph for my first novel. It's from Wordsworth’s “Intimations of Mortality,” and I never remember poetry, but to paraphrase, it’s like, “Heaven lies about us in our infancy. Shades of the prison house begin to close upon the growing boy.”

I love it.

It's so hard to live. Buddhism is all about liberating yourself, in a sense, and it's a lifelong process. We all create our own prisons, if we have the benefit of being born into a society where we're not necessarily just struggling to eat and survive and not be killed. This is somewhat of a bourgeois problem, I guess, but it's not just a bourgeois problem because Buddhism goes back 4,000 years. People have been questing to liberate themselves for a long time. It's just not capitalist society where you have leisure time. People have always wanted to make the most of their time on this planet and find meaning. So, I think by the fourth book, Doll is like… “Okay, things are a little calmer. How do I have meaning?” Because he's very much an outsider. He struggles to be close, really, to anybody—except to his dog. And I just saw you have a cat there behind you.

That's Henry, my orange man. He's my George. I'm pretty sure he's the reincarnation of my grandfather.

Interesting. I wouldn't be surprised. I feel something similar about my great-aunt who I was very close to. Actually, the story I ended up writing for Lee Child was from when I did a deathbed vigil with my great-aunt. She was kind of like my grandmother. I looked after her for years in New York. Anyway, she was supposed to pass within hours. I won't go into the whole thing, but I ended up spending six days with her in a nursing home. I didn't leave her side. I feel that sometimes she's in my dog or I see her in him. I got him a few years after she passed, but she might've been waiting. And sometimes I see her in my girlfriend's dog, in her eyes. Or maybe we just look for it there. Who knows?

Henry will sit on my chest every night. He sits on my chest and just gazes into my eyes, and I feel a deep communication coming through. I'm usually very stoned when this is happening, so I don't know if I'm fantasizing or what, but I feel like maybe it's my grandfather being able to communicate the kind of love that he, as World War II vet kind of guy, wasn't able to communicate in his human form. It was too vulnerable or embarrassing. Anyway, tangent.

No, I hear you. My great-aunt made it to 101 years old. In the last year or so of our relationship, or two years maybe, there was a lot of just sitting in the nursing home where I think she was getting less and less verbal, where it just pleased her to look at me or for us to look at each other. We'd just be sort of silent together. Actually, that entered into my novel You Were Never Really Here, because the main character talks about this with his elderly mother. It’s like sign language, just the slightest movement of the eye. I think I was channeling my great-aunt into that, and that was before she passed. But yeah, so your cat on your chest looking in your eyes… I One time I had a cat adopt me. It was my landlord's cat, but it liked to stay in my apartment. I lived in a walkup in Brooklyn for 17 years, and the landlord was my friend, and I didn't really have a lock on my door. I was just on the third floor, and I had to walk through their house and they could close the doors to the first two levels if they wanted privacy. I was on the third floor, but there wasn't even a lock and the door was kind of flimsy. That cat, when I would come home, he would race out of their living room and run up the stairs to hang out with me, which upset them because he had chosen me. But they had also adopted another cat, so I think in a sense he had felt like, ‘Okay, you guys got this other cat.’ He didn't get along with it, and so he would come up and be with me. His name was Minimus. Oh, he's right behind me in that photo. Oh, Minimus. He died years ago.

Oh God, he's great. A tuxedo.

And my landlords, when they came to visit me in LA—she's an artist, by the way, a great artist, if you want to look her up, her name is Nina Katchadourian and her husband was Sina Najafi who started Cabinet Magazine—

Wow. Yeah, I remember Cabinet.

It was quite the nice house to live in. I mean, in terms of the arts going on. But, so, Nina made this cutout so that I would have Minimus with me in LA. He used to sit on my chest and drool on me.

Oh, and Walter the cat does that in the new Doll book.

Right! So, he would stare into my eyes like you're describing, and then drool on me, and then get on the pillow next to me when we'd go to bed. My apartment was so messy; he liked all the dirty papers he could nest in.

Cats are empathic. I’m sick a lot, and I've been calling mine my Nightingales. They hang around and just kind of purr on me and it's very healing. Anyway… Are you familiar with Charles Williford?

I have one of his books. I have it right here. Which one? I think I've had it for years. Every now and then I pick things up and I try to read them.

He wrote a bunch of freestanding pulp novels that're all great. Cockfighter might be the most well-known one. It’s about a guy who is a cockfighter in the southern circuit, and he takes a vow of silence and it's all modeled after The Odyssey. I wrote an intro to an edition of that a few years ago. I can send it to you if you want to read it.

Oh, yeah.

I'll get your mailing address later. So, Willeford wrote all these freestanding things. Then, later in life, he wrote a book called Miami Blues, which featured a detective named Hoke Moseley, and his agent saw that book succeed and said, “Charles, stick with this. Write a series. You're going to make a lot more money. Write another Hoke Moseley book.” And Willeford was so resistant that he wrote a second book in which the character murders his two daughters so he can go to jail to have some peace for the rest of his life.

Oh my God.

He called it Grimhaven, and he turned it into his agent, and his agent said, “Are you fucking kidding me? No.” So Willeford relented and instead he wrote three more books that were actually continuing the Hoke story. The one where he kills his daughters was squashed, although I have a PDF of it, and it's very good. So, what I'm getting at in a long-winded way is: How do you feel about having a series in your repertoire now?

Well, I'm three books in and I kind of can't believe it. I have career dysmorphia or something. Because I never felt secure as a writer. This guy in college, this very imperious grad student, said to me once, “You're not a natural writer, Jonathan.” I never could let go of that. I struggled with grammar, and I still do, and this and that, but nevertheless, it's like, wow, somehow I've written a trilogy, and now I want it to continue. I love series because I love to get to know a character very well. This Saxon Stories series by Bernard Cornwell that I mentioned earlier? He called his main character Uhtred. It became a TV series, and you get to spend 12 novels with him. I was sort of was bummed that it ended. And then Lew Archer, there are 18 books of Lew Archer2; Richard Stark, 24 books of Richard Stark. But I’m mentioning all noir by men.

What’s a noir by a woman you’ve recently enjoyed?

I just read Dorothy Hughes’s In a Lonely Place. Oh, that's brilliant. Talk about psychological insights. It became a Bogart movie that has no resemblance to the novel. Barely any. The novel was probably too dark for the late forties. It's basically about a serial killer. It was incredible. The insights into that character are amazing. Anyway, yeah, I'm really enjoying having a series because, like I said earlier, I don't have to reinvent the wheel. I know this guy and I can kind of build on what I've done before and I can express things about the world that maybe I want to express through him. I used to talk, on my TV show3, about sneaking in these occasionally profound or poetic statements amidst the burden of writing a comedic half-hour. In the same way, I love having Doll as a vehicle. I kind of see the Doll books as these things where I’m having a very scary dream, and luckily it's not my dream, but it keeps going and I just keep having anxiety. I think these books are probably an expression of my profound anxiety turned into metaphorical situations. My anxiety is all phantom—that something's coming for me, that I've done something wrong, that I'm going to be punished, that I'm in trouble. These are all classic phantom anxieties the mind creates, and whether through Buddhism or analysis you try to work with them to suffer less. It's not easy. The Buddhist writers will tell you it's not. I mean, maybe a few people get to enlightenment but even then, part of the way to get to enlightenment is to suffer and be confused. It's not like you can ever escape painful feelings or painful situations or change or unexpected things or people changing. So, the books are these metaphors for anxiety.

That's very interesting because it makes me think of this sort of chestnut that gets thrown around in addiction recovery, which is that addicts take all their problems and anxieties and they coalesce them into one thing, which is to get your fix every day. In a way, that's more manageable.

That's what I'm saying. I think maybe, in the end, Doll makes it, or he is okay, or he survives, or he gets the bad guy. So, in some sense it's a better experience than life. The hero triumphs. I mean, I like heroes. Doll wants to do the right thing. He's not a bad guy, and I’ve set it up so that when he does kill people, it's in self-defense and usually not intentional. It's like he's almost had no choice. He's in such a dire battle, whether someone's on his back and he's flying down a set of stairs, or he is on a balcony and they're trying to throw him off and he throws them off instead. And then, as you saw in the third book, it's like he can't take that anymore.

And even when—I forget if it's the first or the second book—he gets accosted by two football player types in a parking lot outside his office, and he takes them down with his steel baton very efficiently… he then calls 911 for them. There's a sort of aftercare, as if it were BDSM.

He doesn't necessarily seek out violence, but he's in this difficult profession for someone who would like to be nonviolent. I think what just came to mind, and I don't know if it’s related right to this moment in our dialogue, but there's this great passage in the play Our Town, It’s Emily's monologue at the end of the play, which has stuck with me my whole life. I was actually in that play in high school. I was thinking that I've got to work it into Doll. Maybe he was in that play. But Emily, she's died but she gets to go back for one day and they're all running around the house getting ready for school. And she's like, “Mama, just stop. Just look at me.” And Mama doesn't. And then Emily says to the narrator, who's like an angel figure in a sense, “God, it's all so painful. Does anybody ever stop and just realize how beautiful it all is?” I'll never forget the timing of the way the narrator said the next line when I saw it at Lincoln Center. She asks this big existential question, “Does anyone ever stop and look at each other and see how beautiful it all is?” And there's a beat and then the narrator is like, “No… Well, a few people. Some saints and poets maybe.” I feel like that monologue is at the core of maybe everything I do, and so it is also at the core of my own existence.

I saw a production of Our Town in a tiny theater in downtown New York in the early 2000s, and the moment you’re talking about… I was just weeping like a baby.

Right? It’s like, when I'm with my elderly parents, can I stop and just see them? It's very hard, this current of thinking and life itself and forgetting that everything is mortal and ephemeral. And this conversation, it's interesting. I feel like I've been present. It's been really fun chatting with you and everything. I once was doing a sports piece in 2004 for GQ. I don't know if you had this experience as a magazine writer, but it's kind of Hollywood in a way. There were so many pieces I wrote or started writing that got killed, or I just couldn't see them through because it turned out there was no story. GQ had me do a profile of Terrell Owens.

A simply legendary wide receiver, for those who don’t know.

This was like 2004. I had a thing with magazines back then, because of my essays. I used to write a lot of essays and I wrote for the New York Press. Bukowski was my big role model at the time. The mainstream magazines would come to me and say, “Write something for us,” and then I would, and they'd be like, “This isn't quite GQ.” I'd be like, “Wait, but you said you like my voice. I can't write this standard thing that you're looking for.” So they'd either kill it or sometimes edit it into oblivion. Mostly they killed them.

I prefer being killed to being edited into oblivion. My relationship with GQ ended after I wrote two assigned stories for them, then pitched them a story about a friend of a friend who is a male hustler who does MAGA roleplay tricks for older liberal men. They never even replied to that pitch.

Mostly I got killed and then I would publish them in the New York Press or elsewhere, some alternative journal. But anyway, this one time I was interviewing Donovan McNabb in the locker room at the Philadelphia Eagles Training Center.

That's my team, by the way. Go Birds.

He was really cool, and I felt bad that people didn't appreciate his career enough or it seemed like he got slammed a lot.

He did. I think the issue was mostly about coaching. But anyway, we could get in the weeds on that.

And they almost won that Super Bowl. He gets stopped at the one-yard line or something.

2005, Super Bowl XXXIX against the fucking Patriots.

Yeah. So, Terrell Owens had just joined the team. I went over to Donovan McNabb and I said something to him like, “How do you do this, man? You've got to succeed at this level with these athletes. How do you do this?” He said, “My mother taught me to be the best at everything in every moment of my life.”

Jesus Christ.

He said, “So, right now, I want to give you the best answers you've ever gotten. I want to be the best at all times.” I was like, ‘Oh, my God. Whoa. This drive to be a gladiator with 350-pound dudes running at you... ’ I mean, that's intense. I'll tell you one other quick sports interview moment. It was the New York Observer in this case. They actually did publish me in my voice, but it was before Jared Kushner bought the paper and wrecked it. They sent me to the US Open, which I was thrilled about. I had been a big tennis player growing up. Afterwards, I was in the reporters-pool room. Andre Agassi had just played his first-round match, and he had been paired with—because he was probably number one—this guy who was in his early thirties. He was, like, somewhere in the amateur/pro gray zone and he somehow got the number-99 seed. He had never played in a pro tournament.

There are those pro-ams who get in every year. They’re like cannon fodder.

Cannon fodder. Agassi beat him, of course. He got annihilated. So, I raised my hand, and I asked Andre Agassi: “Did you feel bad at all about beating this guy?” He answered, “I'm not going to deny him what he was meant to learn from that.”

Whoa. That is some alpha shit right there.

But also it was, like, respect too. It was a really good answer.

I love it. So, another question: Do you know anything about the reception for the Doll books from the classic-crime audience?

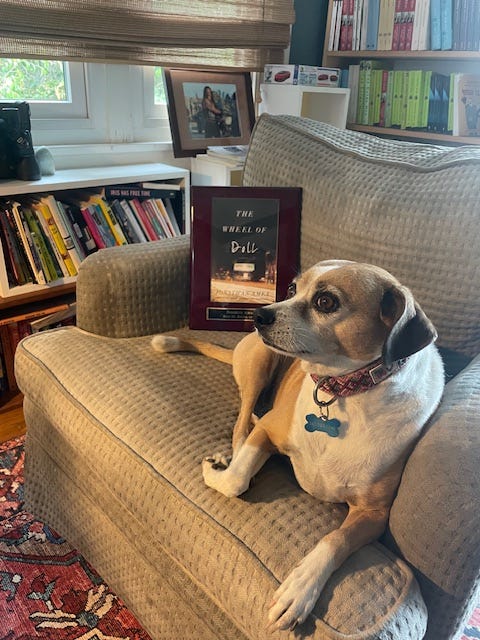

Great question. I still don't know that I have totally reached the larger crime audience that is out there reading people like S.A. Cosby, Dennis Lehane, or Megan Abbott. These people are well-known in that world; they've been in that world from the beginnings of their careers. The crime audience that I've encountered—I've gone to two conventions. The Wheel of Doll won this award, the Shamus Award for Best Private Eye book of 2022.

Amazing.

I was so honored. I have the plaque right here.

Oh, that's so cool. That's great, man.

It's beautiful. And then, also, and this wasn't maybe one of the bigger awards, it was from the Private Eye Writers Association of America, and I feel like maybe I haven't been gracious enough about that. I should join it, which I probably will. I need to join, become a member. Maybe it's 50 bucks a year, you get a newsletter or something. They were so nice to me, and it was held at a pizza parlor, and it was sort of coming out of COVID, and there were maybe 30 people there, and I won. I couldn't believe it.

Here endeth the lesson. Please read the Doll books by Jonathan Ames. And read his gut-punch of a short novel You Were Never Really Here. In fact, read everything by him! And thanks, Jonathan, for your time and generosity in conversation with me.

— Jesse Pearson

As in the Parker novel series by Richard Stark, a precedent for the Doll books and definitely things you should read too.

The protagonist of an incredible series of novels by Ross Macdonald. Read these too.

HBO’s Bored to Death.