Find the first installment of this post here.

Now we find Lee Lozano swerving from an art of pure imagery to an art totally devoid of pictorial representation and, instead, one built solely with words. Lozano was masterful at deploying language. In pieces that were simply descriptions of pieces, she made puns, utilized invective, and deployed poetry.

These came to be known as the ‘Life-Art’ pieces, or sometimes the Language Pieces. Across the span of eleven notebooks, Lozano, in addition to diaristic writings and banal notes-to-self, put down the blueprints for works that, if not qualifying for Conceptual Art, are at least cousins to it. There are more than eighty pieces named in her notebooks; twenty of those were elevated to incarnations on graph paper.

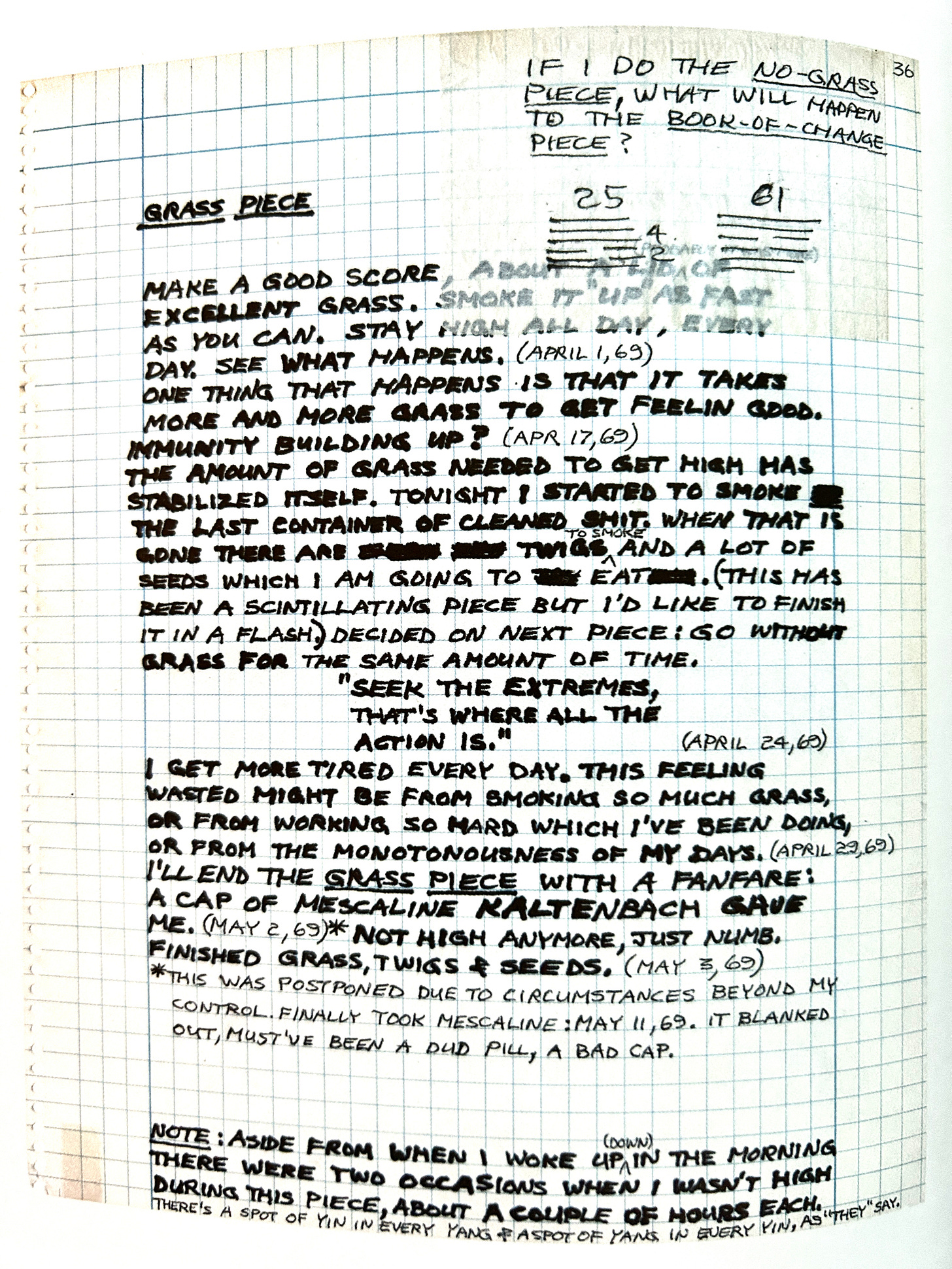

Let’s look, for example, at Grass Piece from 1969, in which Lozano makes a “GOOD SCORE” of some “EXCELLENT GRASS” and then proceeds to “STAY HIGH ALL DAY, EVERY DAY, SEE WHAT HAPPENS.” (Spoiler: she gets “MORE TIRED EVERY DAY.”) For Lozano, a heavy user of pot, this piece might have been the self-administered equivalent of the clichéd parent-forcing-a-child-caught-smoking-to-smoke-an-entire-pack-of-cigarettes trope. But, being a soldier for the cause, Lozano powers through, inveigling her cannabis-loving self to:

“SEEK THE EXTREMES

THAT’S WHERE ALL THE

ACTION IS.”

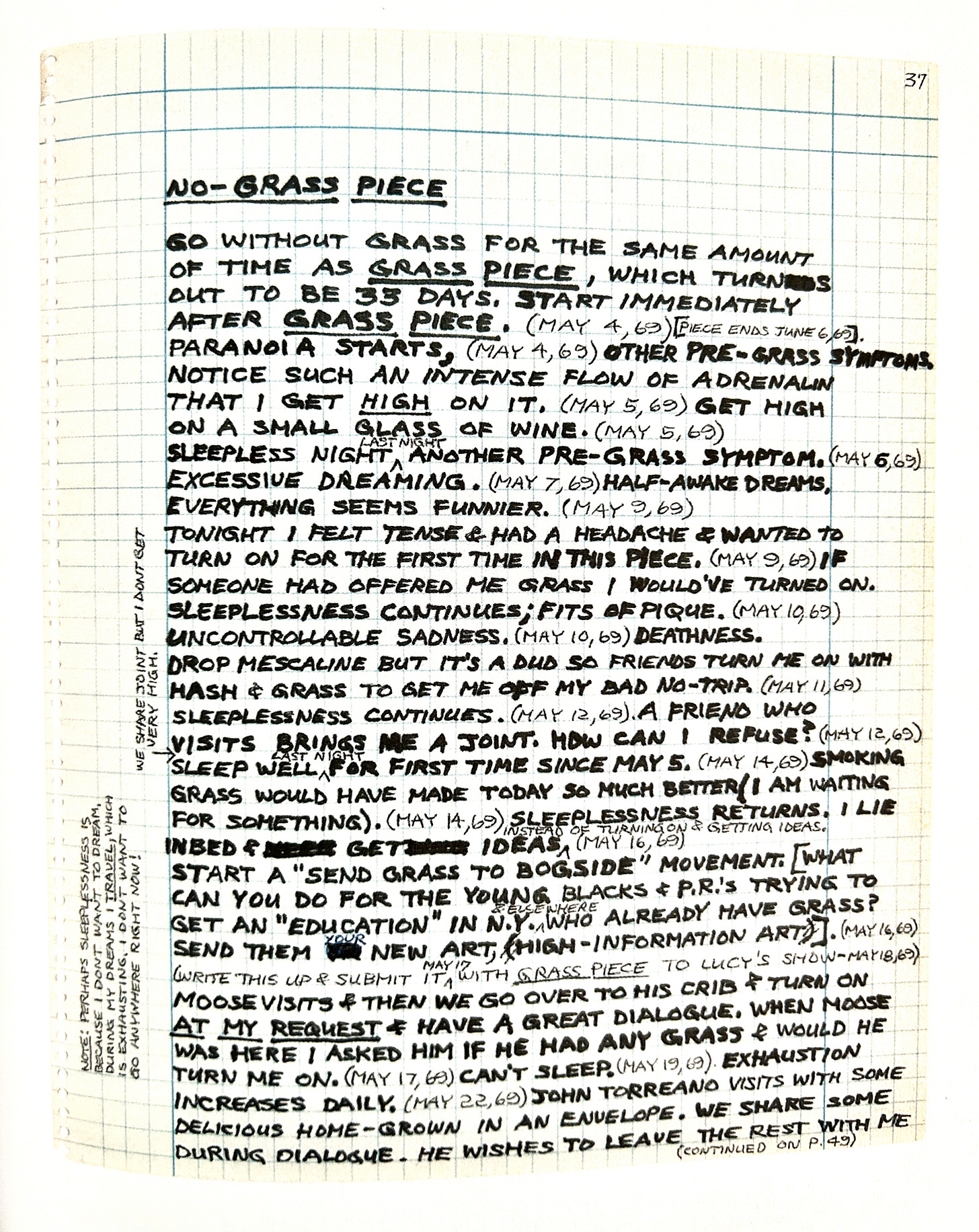

The opposite extreme follows Grass Piece. It is, logically, No-Grass Piece, 1969. Having remained zooted for 33 days straight for the first piece, Lozano now must stay straight for 33 days straight for the second piece. She writes in this piece of “SLEEPLESSNESS” followed by “EXCESSIVE DREAMING1” and complains of tension, headaches, “FITS OF PIQUE” and “UNCONTROLLABLE SADNESS.” We can only conclude, based on her findings, future behavior, and the fact that Lozano didn’t make it 33 days, that she elected to continue down the marijuana trail once this piece’s timeframe was concluded.

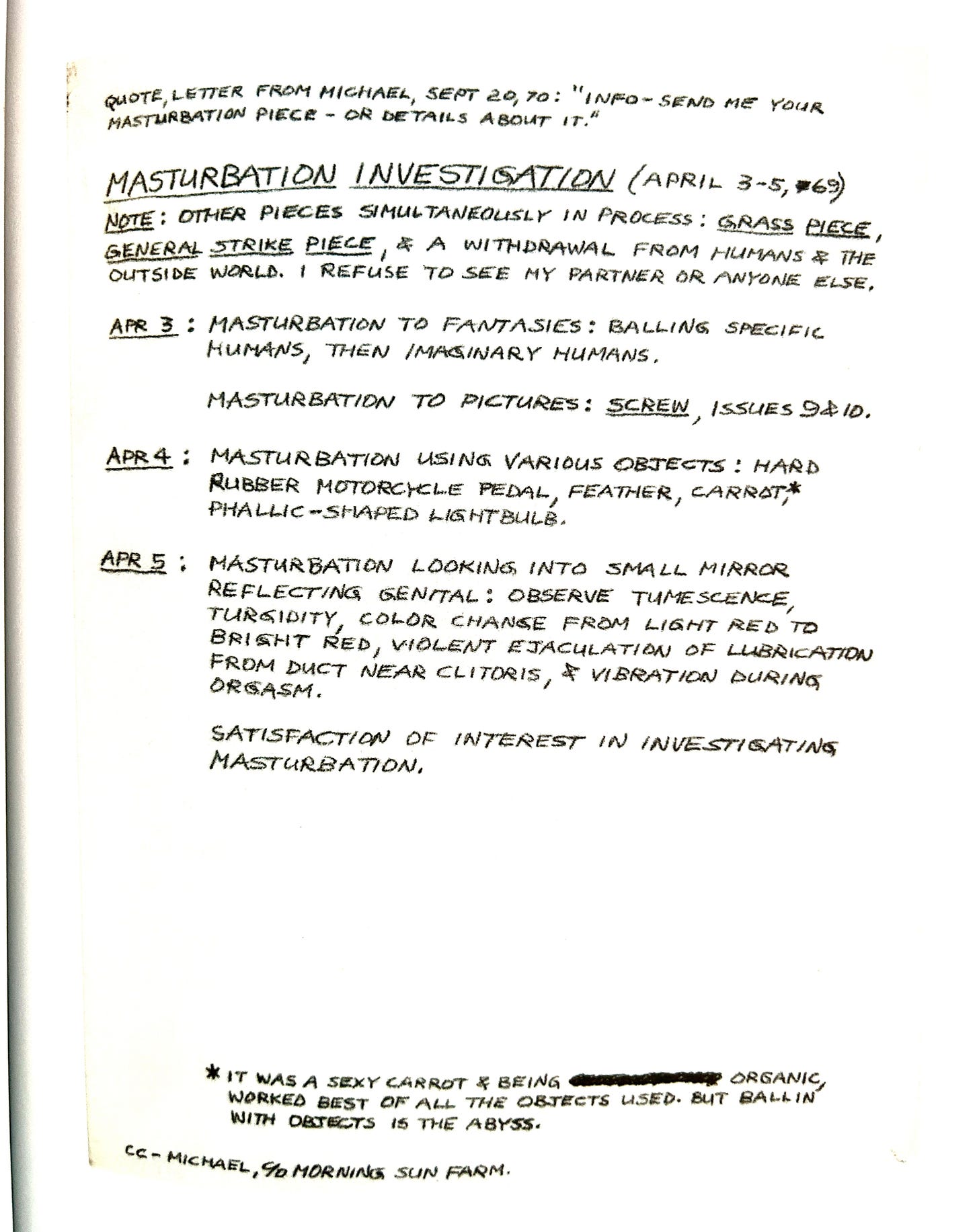

Another piece from this era, and an even more revealing one, is Masturbation Investigation, 1969. Running concurrently with Grass Piece (and involving a foreshadowing “WITHDRAWAL FROM HUMANS & THE OUTSIDE WORLD”), this piece took Lozano through three modes of masturbation over three consecutive days. First, she masturbated to fantasies (“BALLING SPECIFIC HUMANS, THEN IMAGINARY HUMANS” and also utilized pictures—namely, a copy of Screw magazine). On the next day, she introduced objects (“HARD RUBBER MOTORCYCLE PEDAL, FEATHER, CARROT2, PHALLIC-SHAPED LIGHTBULB”). On the final onanistic day, Lozano masturbated while looking into a mirror that faced her crotch, observing “TUMESCENCE, TURGIDITY, COLOR CHANGE FROM LIGHT RED TO BRIGHT RED, VIOLENT EJACULATION, & VIBRATION DURING ORGASM.” This piece is a retort, perhaps, to philistine criticisms of contemporary art being a form of mental masturbation.

These three pieces have to do with many people’s daily life activities, albeit ones related to pleasure. But there’s something light in their quasi-scientific probings into things that are often left unexamined. Many of Lozano’s proposed pieces, which didn’t make it beyond their titles, are in a similar vein: Stop Smoking Cigarettes Piece, The Lie-In-Bed-All-Day-And-Read-Comic-Books Piece, The Get-Fat-And-Lazy Piece, Keep Your Asshole Virgin Piece, and The See-How-Long-You-Can-Go-Without-Making-A-Call Piece3. Other ‘Life-Art’ pieces hint at more serious thoughts and aims.

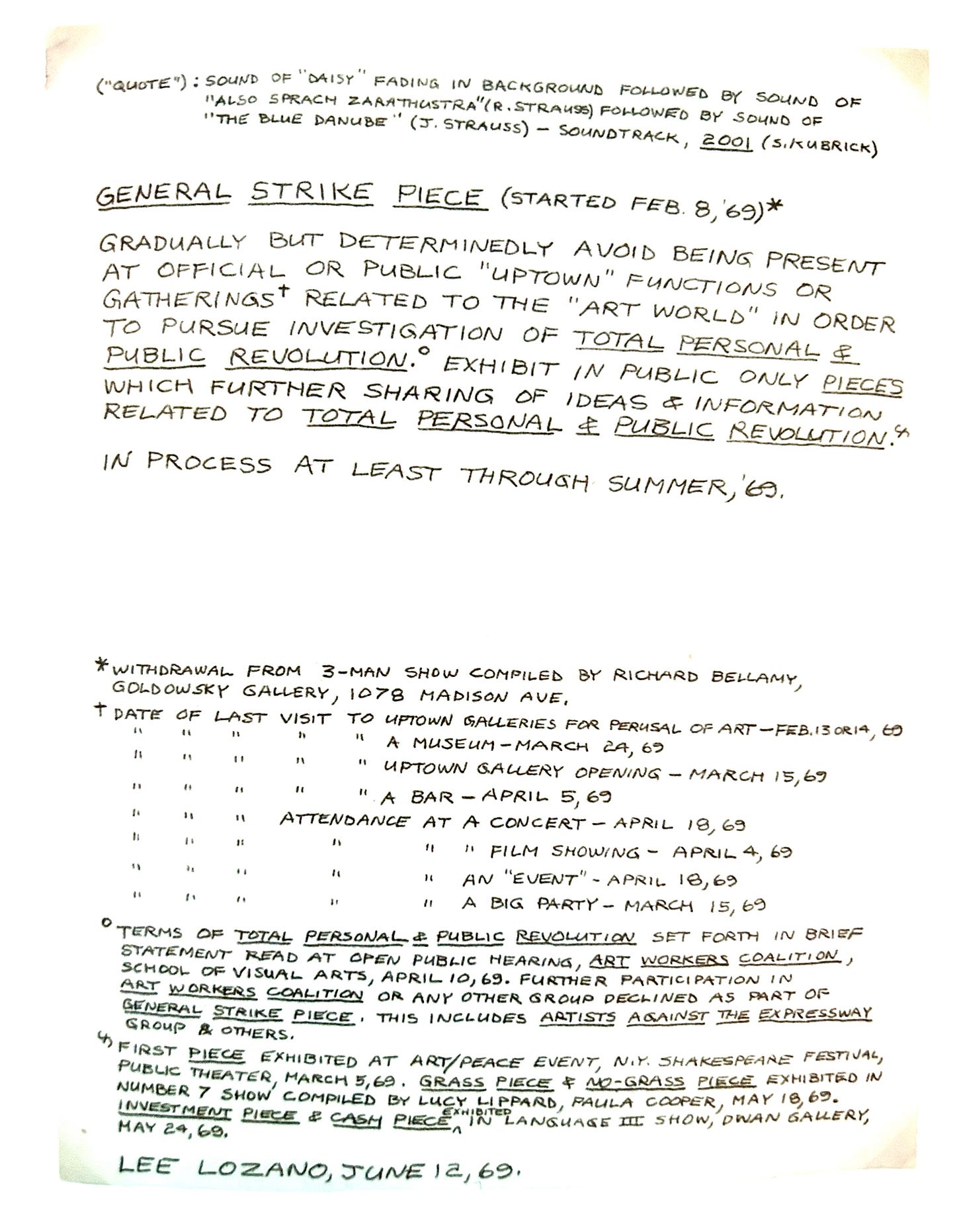

General Strike Piece, 1969, saw Lozano beginning the process of divorcing herself from the milieu in which she’d been immersed for the past decade. “GRADUALLY BUT DETERMINEDLY AVOID BEING PRESENT AT OFFICIAL OR PUBLIC ‘UPTOWN’ FUNCTIONS OR GATHERINGS RELATED TO THE ‘ART WORLD’ IN ORDER TO PURSUE INVESTIGATION OF TOTAL PERSONAL AND PUBLIC REVOLUTION.” This statement was made as she was preparing to mount a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum the following year4.

DECIDE TO BOYCOTT WOMEN might be the Lozano piece you’ve heard about even if you haven’t heard about her. Starting with that simple declaration in a notebook in 1971, Lozano indeed went on to, with few exceptions, not talk to another woman for the rest of her life. Plenty of ink has been spilled over that one, so I’ll refrain here.

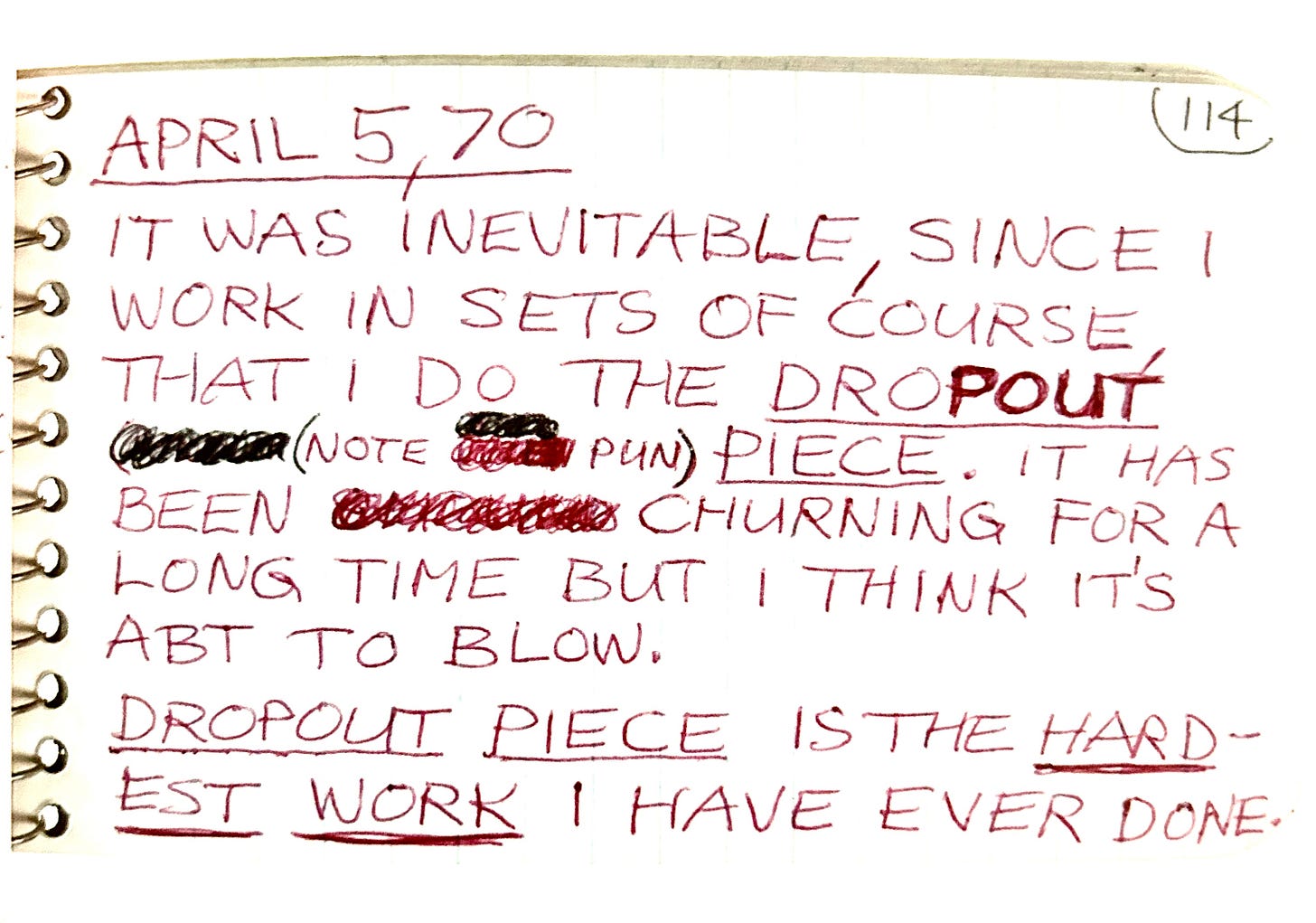

And then comes Dropout Piece, 1970 or maybe 19725, which Lozano wrote was “THE HARDEST WORK I HAVE EVER DONE.” It entailed nothing less than leaving the art world completely—and she did just that. This was not tantamount to, say, quitting a job; it would be more like quitting a life, killing a version of her self. Dropping out, at the tail end of hippiedom’s heyday, was still in the air in America. But the Timothy Leary mode of dropping out involved sacrificing one orthodoxy—square life—for another, equally prescriptive one—countercultural life. And though Lozano was, at this point, a voracious vacuum for LSD, your garden-variety hippie would be out of his league amidst the sort of behavior Lozano aspired to:

START LIVING AT MORE RANDOM HOURS. DESTROY SCHEDULES. SLEEP, EAT, GROOM, TAKE VITAMIN PILLS ETC IRREGULARLY TO BUILD UP RESISTANCE TO HABIT-FORMING, TO MAKE LIVING MORE INTERESTING & FLEXIBLE.

We’re used to the idea of an aspiring artist being hungry for recognition. Along with recognition come the fringe benefits of fame and money. These are the golden rings that the cannon fodder of the art world are reaching for. Lee Lozano had these things in her grasp. She’d pretty much made it, and that was the point at which she decided to walk away. “I will not seek fame, publicity, or suckcess,” she wrote. After 1971, Lozano becomes ghostly. Appearing here and there in friends’ lives, couch-surfing, perhaps at some points homeless… she whittles down her very identity, changing her name to Lee Free, then Leefer, and then simply E. She avoids not just the art world, but the world world. “MAKE SOLITUDE VALUABLE,” she writes, and, “I WILL MAKE MYSELF EMPTY TO RECEIVE COSMIC INFO.” She shows up in the early punk scene; she’s spotted at CBGBs. Apparently she dances a lot. Then, New York’s largesse depleted, she moves to Dallas, where she lives with her parents. Her dad gets a restraining order against her as her behavior becomes more erratic. She moves into another apartment in the same building. She dies of cervical cancer in 1999. She is buried, in accordance with her wishes, in an unmarked grave.

Was Lee Lozano mentally ill? Was she an acid-besotted malcontent? Who cares, at this point? She was one of the most brilliant artists of the twentieth century; she was lightyears ahead of her time in both thought and action. She was brave. And we can learn something from her today. Contentedness is a trap. The pursuit of so-called success never really ends because there are always more worlds to conquer. Would it be fogeyish if I were to compare the current ambrosia of likes and follows to a microcosmic version of the potential fame that Lee Lozano rejected? We all have the option of dropping out, of refusing to play, of pulling a Lozano.

As any stoner worth their weight in weed can tell you, one of the main symptoms of sudden smoking cessation is the return of dreams, of which you are blissfully unaware when habitually high.

Lozano’s own footnote to “CARROT” in this piece reads: “IT WAS A SEXY CARROT & BEING ORGANIC, WORKED BEST OF ALL THE OBJECTS USED. BUT BALLIN’ WITH OBJECTS IS THE ABYSS.”

This list was cribbed, in the same order, from Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer’s Lee Lozano: Dropout Piece (Afterall Books, 2014), which is one of the most important texts on Lozano and her works. Highly recommended if you can find an affordable copy.

The works in this show, Lozano’s Wave Paintings, grand abstractions that riffed on electromagnetic wave theory, were described in Artforum magazine as having a quality of “oppressive decorativeness” and being “disturbing.” Lol.

There is some debate or confusion around when the piece actually commenced.

so good! thanks for this one.